Automated Identification and Coding of Drug Overdose Records

Background

The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is a principal agency of the Federal Statistical System which provides statistical information to guide actions and policies to improve the health of the American people. NCHS oversees a number of surveys and data collection systems, including the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS). The NVSS works in partnership with state and local governments to collect, analyze, and disseminate data on vital statistics, including birth and death events. This data is used to monitor trends of public health importance such as the ongoing opioid crisis.

Mortality data from the NVSS is currently coded using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), which is used to identify underlying and contributory causes of death. Coding of records for drug involved deaths in particular is a complex process and faces unique challenges, including:

-

Manual coding: NCHS uses automated programs to assign ICD-10 codes for as many as twenty multiple causes of death and one underlying cause of death based on a complex set of rules. In general, the program rejects about one-fifth of death records which must be reviewed and coded by trained nosologists. However, for the estimated 2.6 percent of deaths with an underlying cause of drug overdose, about two-thirds of records are rejected and require manual coding (Trinidad, Warner, Bastian, Minino & Hedegaard, 2016).

-

Incomplete information: Approximately 20 percent of drug overdose records do not include specific drug mentions (Rudd, Seth, David, & Scholl, 2016). This makes it difficult to categorize records as ICD-10 codes are based on specific drugs or broad drug classes.

-

Limited codes for specific drugs: ICD-10 is limited in capturing drug-involved mortality as it contains few codes pertaining to specific drugs (e.g. heroin, methadone, cocaine) and these codes are only applied in specific circumstances. Most drugs are coded using broad categories or drug classes, making it difficult to monitor trends in specific drugs that are not already uniquely classified by ICD-10.

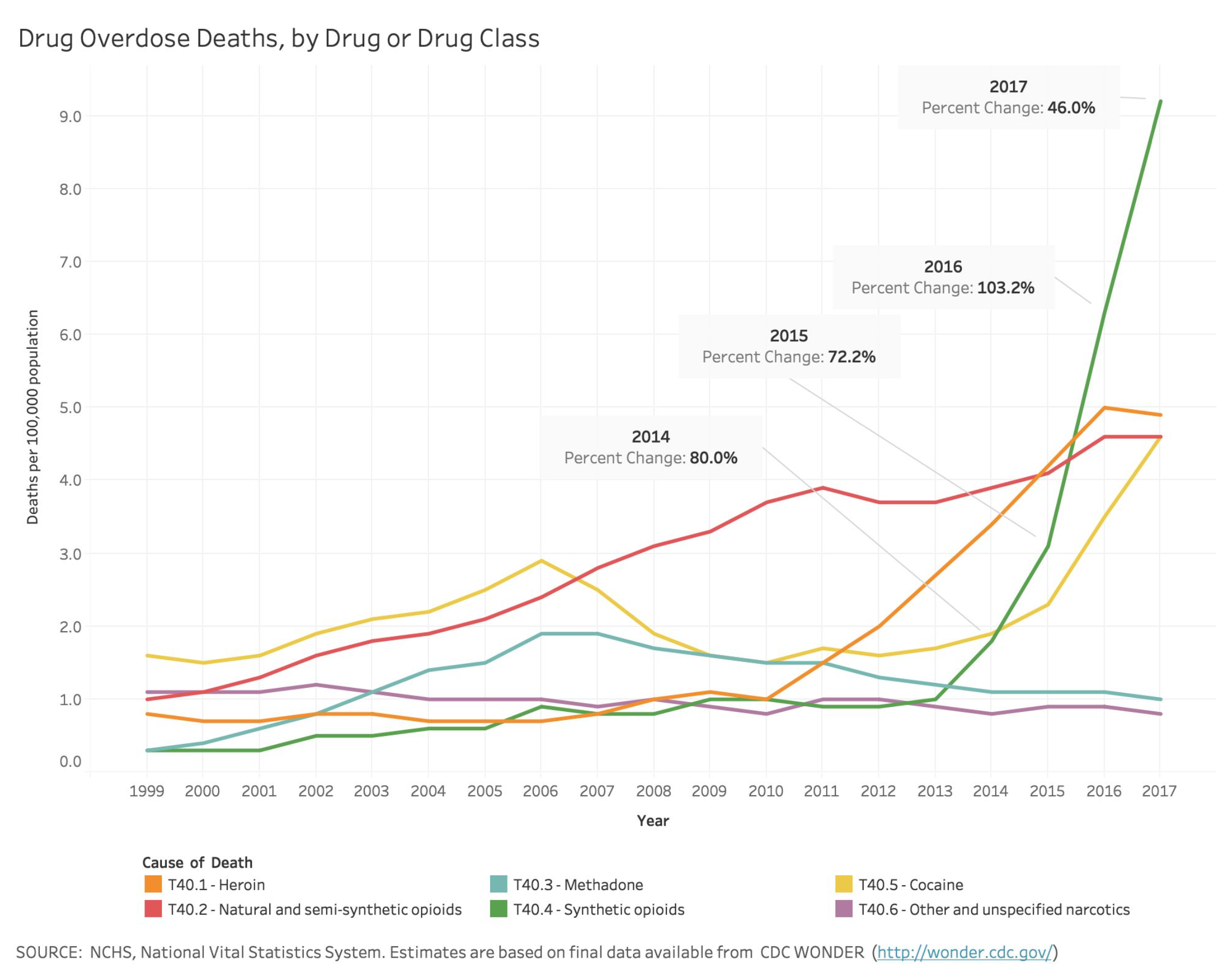

The current state of the organization allows for release of final mortality data once it has been cleaned and coded, approximately 12-months after data collection. Timely release of mortality data for drug-involved deaths is of critical importance, with the opioid crisis currently recognized as a national public health emergency (The White House, 2018). The CDC (2019) reported that in 2017, the final number of overdose deaths involving opioids was 6 times higher than in 1999. More specifically, the age-adjusted death rate due to poisoning with synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl) has increased by a factor of 30. This trend illustrates the need to better understand the specific drugs involved within this broad category.

Prior Work

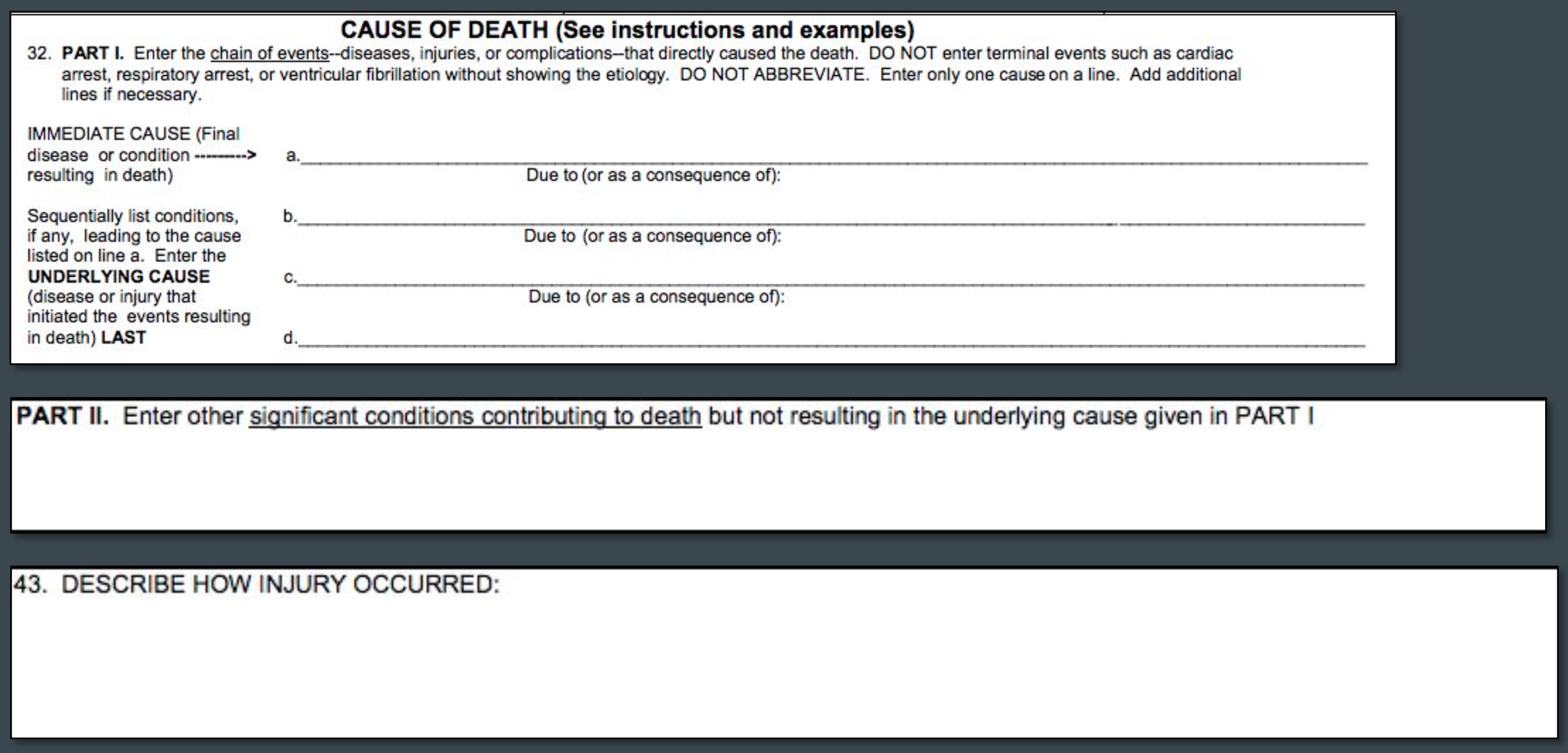

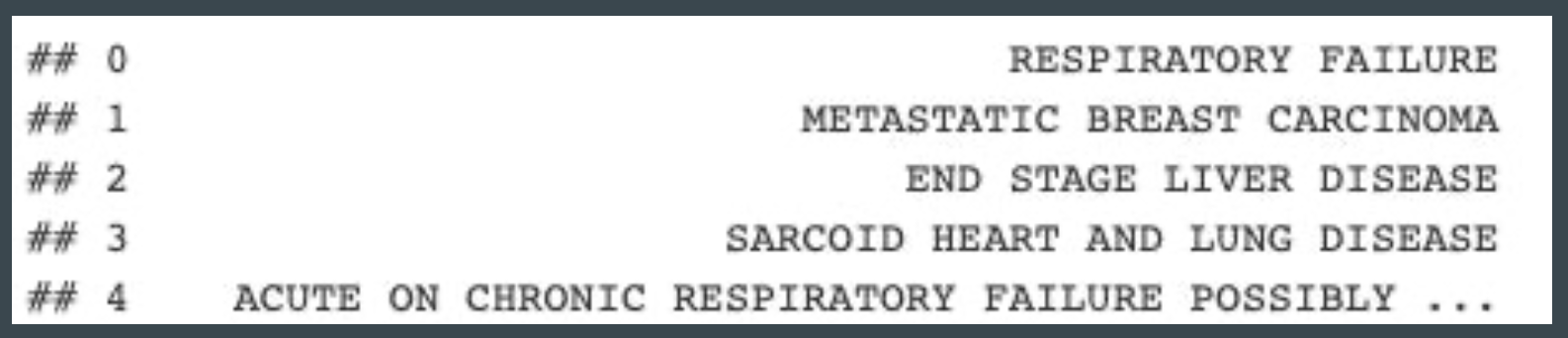

Past work by Trinidad, Warner, Bastian, Minino and Hedegaard (2016) have focused on developing programs to identify records containing drug mentions with involvement (DMI) and to extract specific drug mentions from literal text fields of the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death. These fields include:

-

The chain of events leading to death (from Part I)

-

Other significant conditions that contributed to cause of death (from Part II)

-

How the injury occurred (in the case of deaths due to injuries from Box 43)

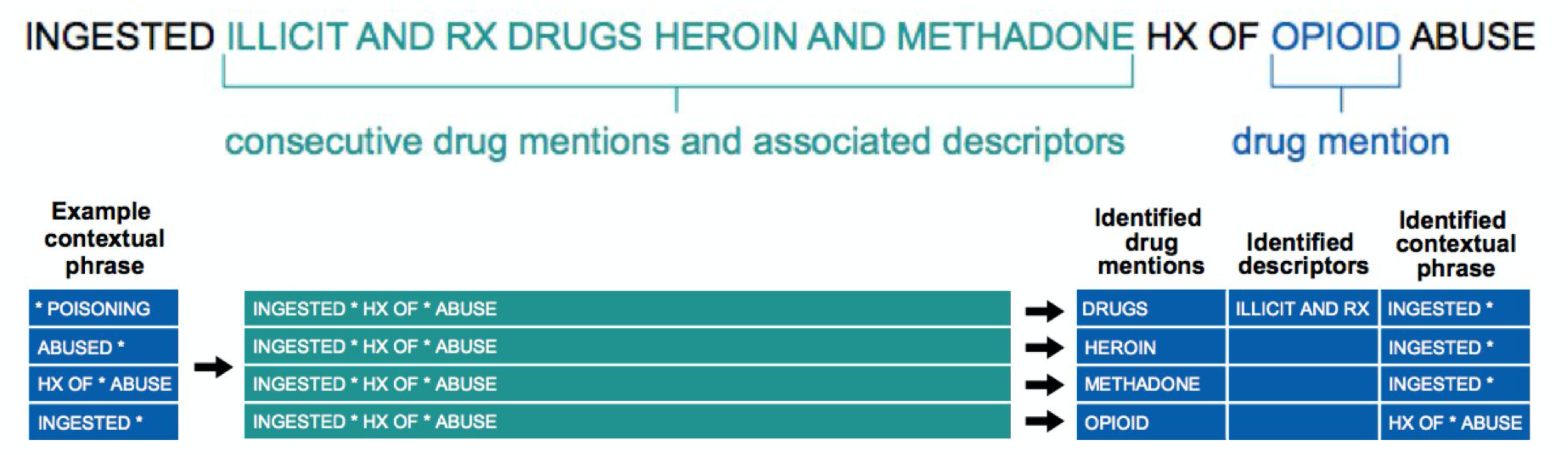

Programs developed rely on exact pattern matching and significant collaboration between NCHS and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop search terms for identified drug mentions, descriptors (e.g., illicit, prescription/RX), and contextual phrases (e.g., ingested, history/HX of abuse) (Trinidad et. al, 2016). Analysis of literal text in this manner is beneficial as it provides an opportunity for an enhanced understanding of the national picture of drug involvement in deaths in the United States. However, the time involved to develop and maintain keyword lists and programs necessary for exact pattern matching is problematic.

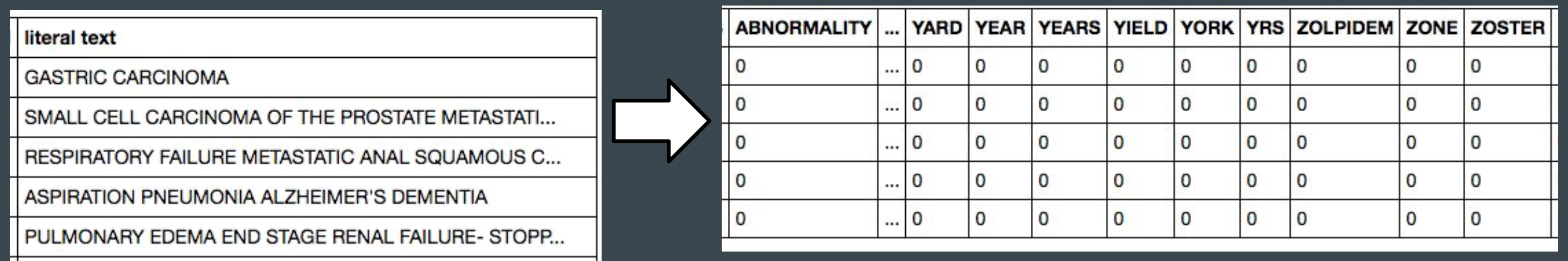

Previous work as part of Loyola’s graduate course in Machine Learning explored the use of literal text to identify DMI records with high precision and specificity. Within the context of the project, a record was determined to include a DMI if the underlying cause or any of the twenty available multiple causes were assigned a code pertaining to drug overdose (i.e. X40-44, X60-64, X85, Y10-Y14). Results from the program detailed by Trinidad et al. (2016) identified DMI records with a positive predictive rate or precision of 95.8 percent. Using this as a baseline, a program was created in Python using basic natural language processing (NLP) techniques to convert a corpus of literal text records into a sparse document term matrix to train a classifier to identify DMI records. The program exceeded the baseline with a precision and specificity for DMI records of 98.6 percent. It should be noted that the results in the program were achieved using publicly available data from the Washington State Department of Health and may not completely reflect the quality of text data from all states and territories. This project will develop a similar model using data for the United States and territories from 2005-2017 available to NCHS.

Research Questions

The focus of this capstone project is centered on three main questions given the problem as defined:

-

Can we use machine learning to accurately identify records with an underlying cause of drug overdose?

-

Can we extend those methods to assign specific ICD-10 codes?

-

Are there better methods for extracting drug mentions, including novel drugs not yet added to expert lists?

Data Sources

The project uses two primary data sources from the NCHS’ National Vital Statistics System. Historic mortality data from 2005-2017 and literal text data files.

The mortality data file includes records of death from all 50 states and territories through 2017. Information in the mortality data file includes general demographics for the decedent, data year, and a variety of codes pertaining to a single underlying cause of death and up to 20 multiple causes of death. Detailed documentation on the public use data files are provided by NCHS (2018). Public use files are provided by year and fields may be added or removed over time. For the purpose of this project, the specific fields requested were ICD-10 codes pertaining to underlying and multiple causes of death and the manner of death field which is related to the intent of death. All other fields were dropped from the provided data files.

- ICD-10 Codes

- Multiple causes of death

- Underlying cause of death

- Manner of death

- Accidental

- Intentional

- Homicide

- Undetermined

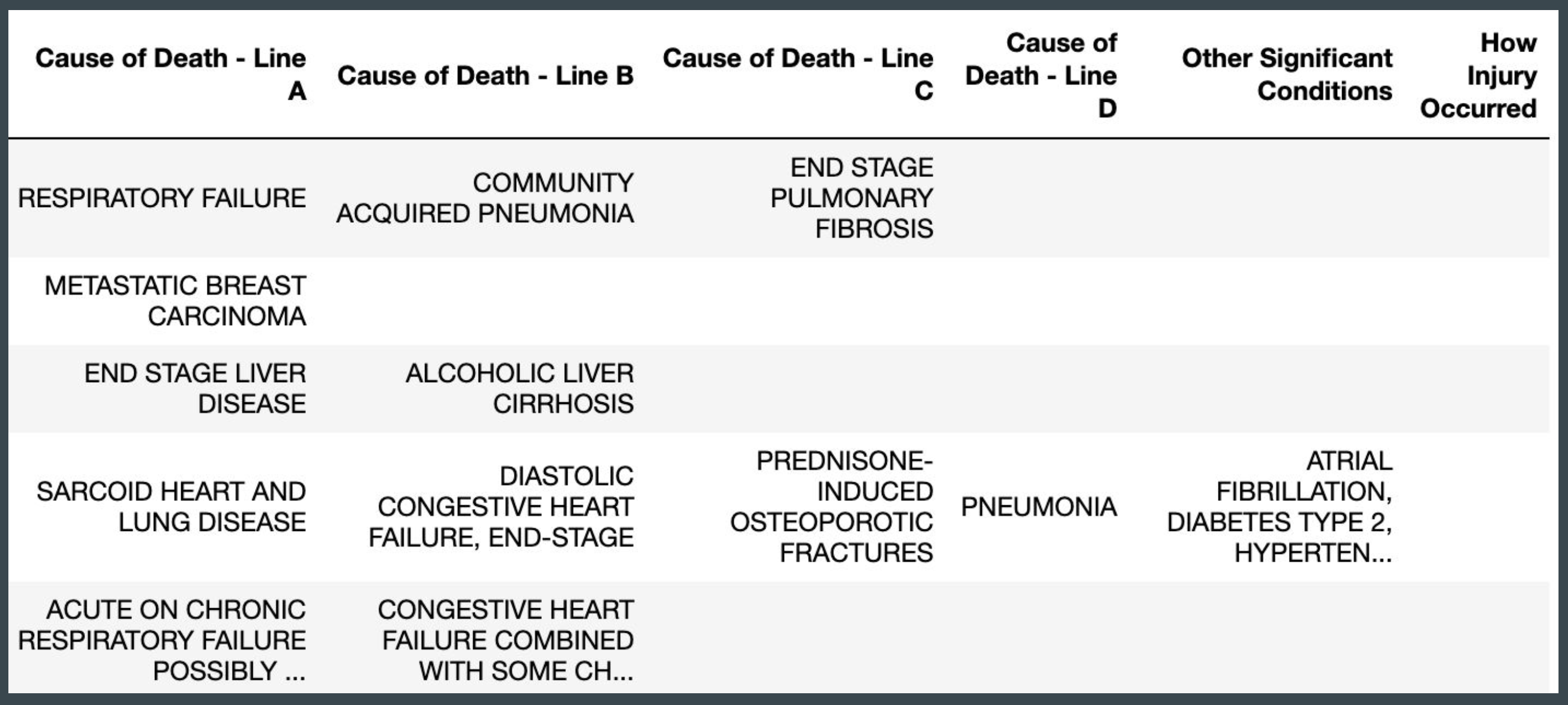

The literal text files include text as entered by a physician, medical examiner, or coroner on the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death. Variables from the literal text file include the chain of events leading to death (from Part I, Lines A through D), time intervals for each event in Part I, other significant conditions that contributed to cause of death (from Part II), how the injury occurred (in the case of deaths due to injuries from Box 43), and place of injury. For the purpose of this project, only fields containing literal text for Part I, II, and Box 43 were requested. All other fields from the literal text files were dropped.

A Quick Primer on ICD-10 Codes

Multiple cause codes within the mortality file may be used to indicate cause of death as well as specific substances or broad drug classes contributing to the cause(s) of death.

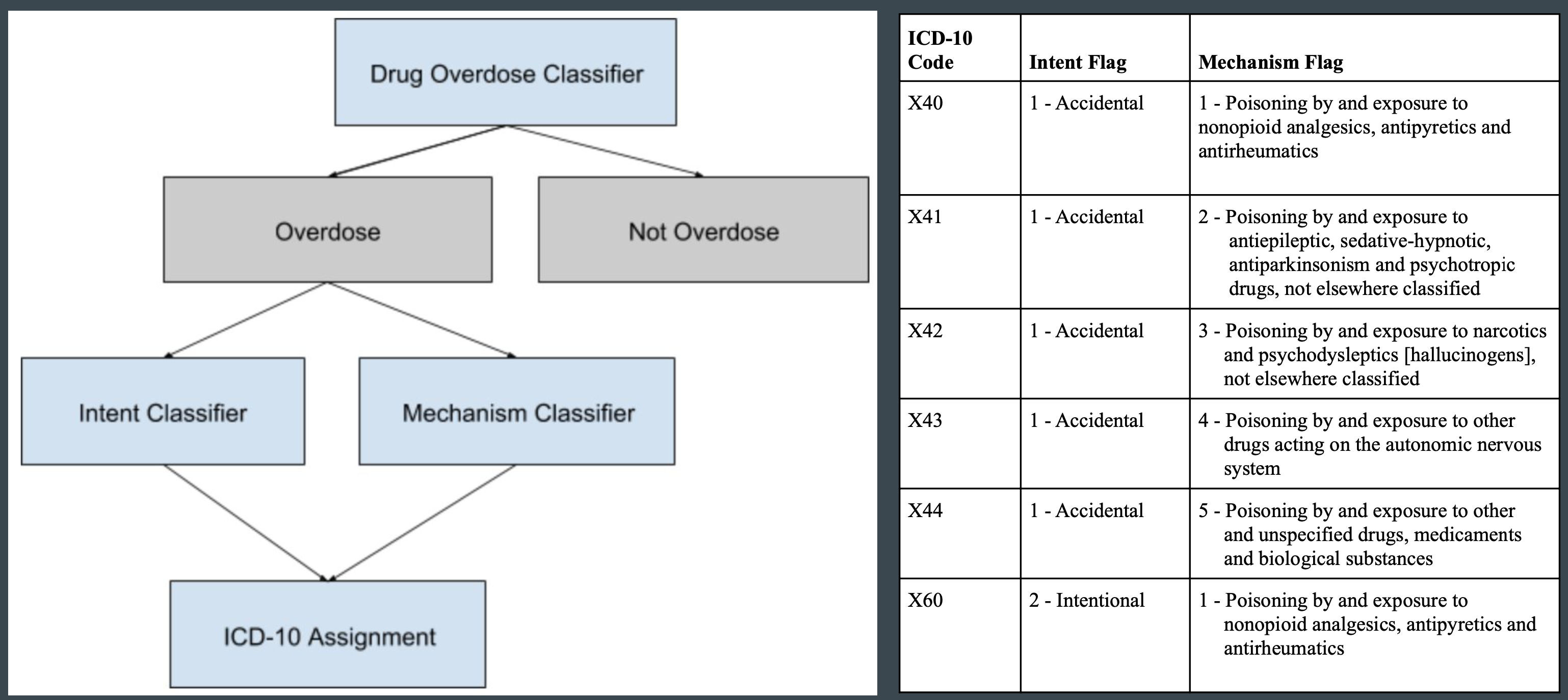

- ICD-10 codes for drug overdose as underlying cause of death are characterized by intent and mechanism:

- X40-X44

- X60-X64

- X85

- Y10-Y14

- Additional T, F, or R codes may indicate specific substances or broad drug classes

- T40.1 - Heroin

- T40.4 - Synthetic Opioids

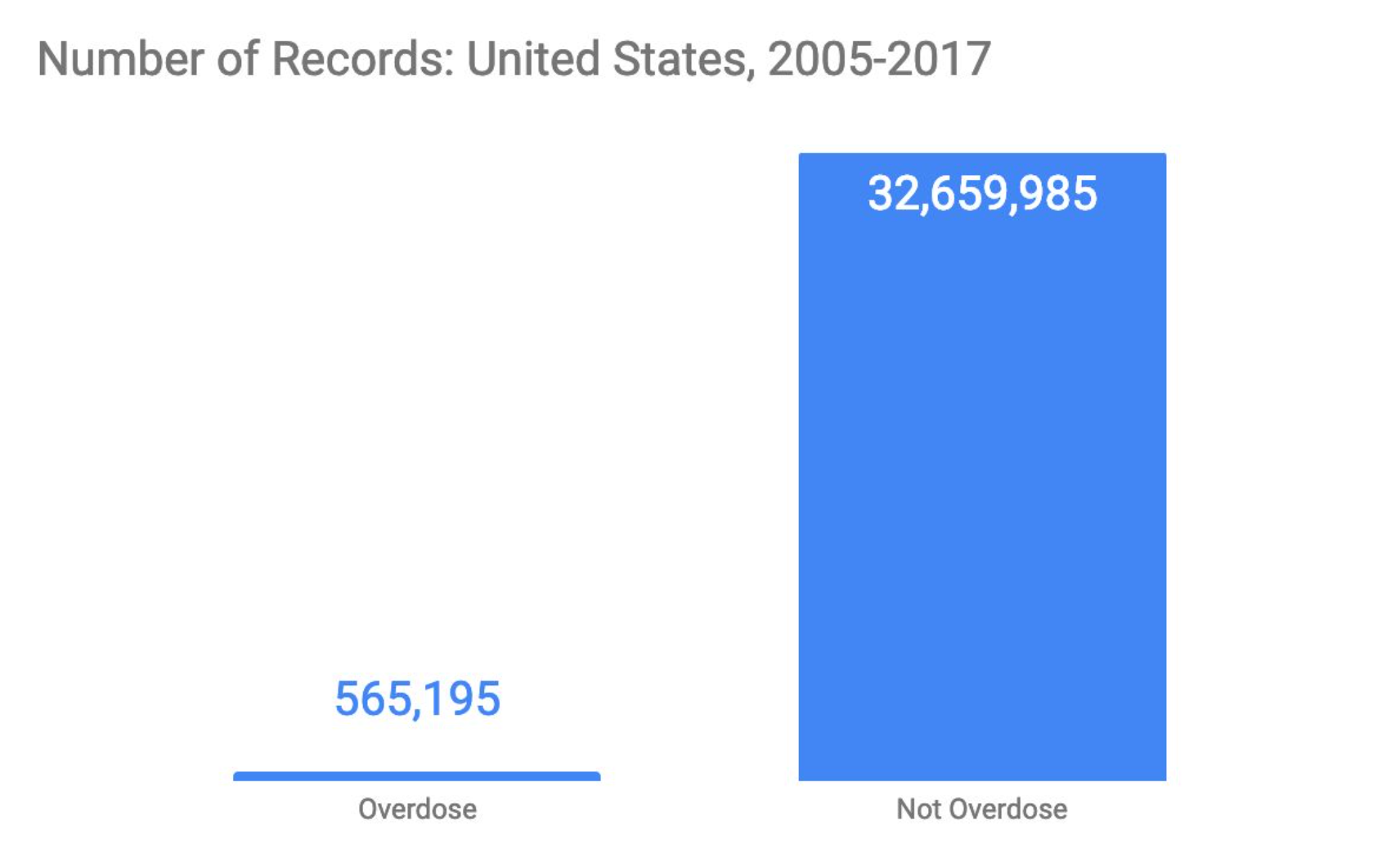

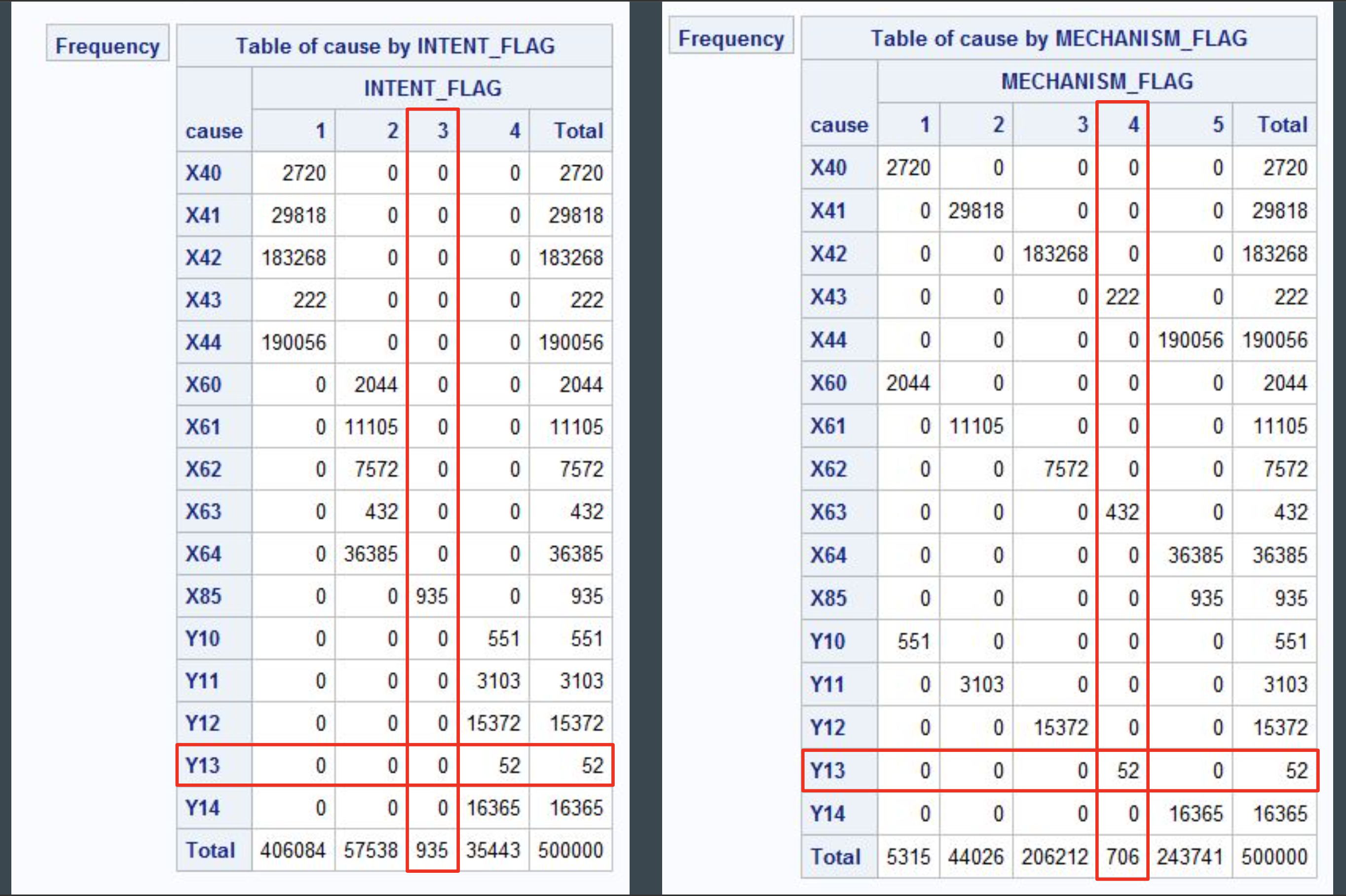

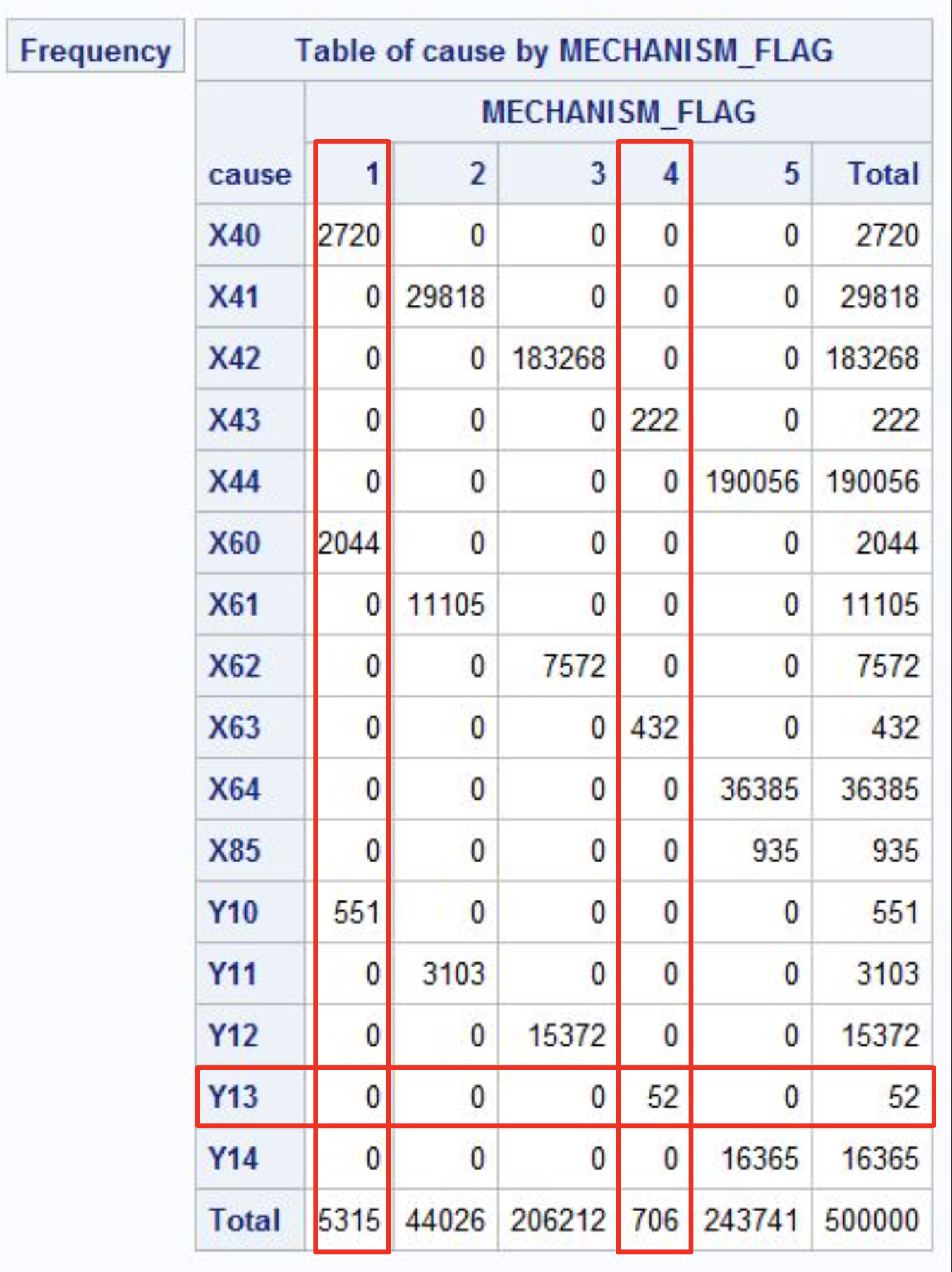

Running some cross tabulations for records by ICD code and variables such as intent and mechanism, it is observed that there are significant class imbalances which must be accounted for when developing predictive models.

Primary Objective: Identify and Code Drug Overdose Records

Given the heavy class imbalance within the datasets, the metrics of interest for model comparison and selection will be precision and recall. Precision determines the proportion of records assigned to a given class that were correct. minimizing false positives. Recall determines the proportion of records belonging to a class that were correct, minimizing false negatives.

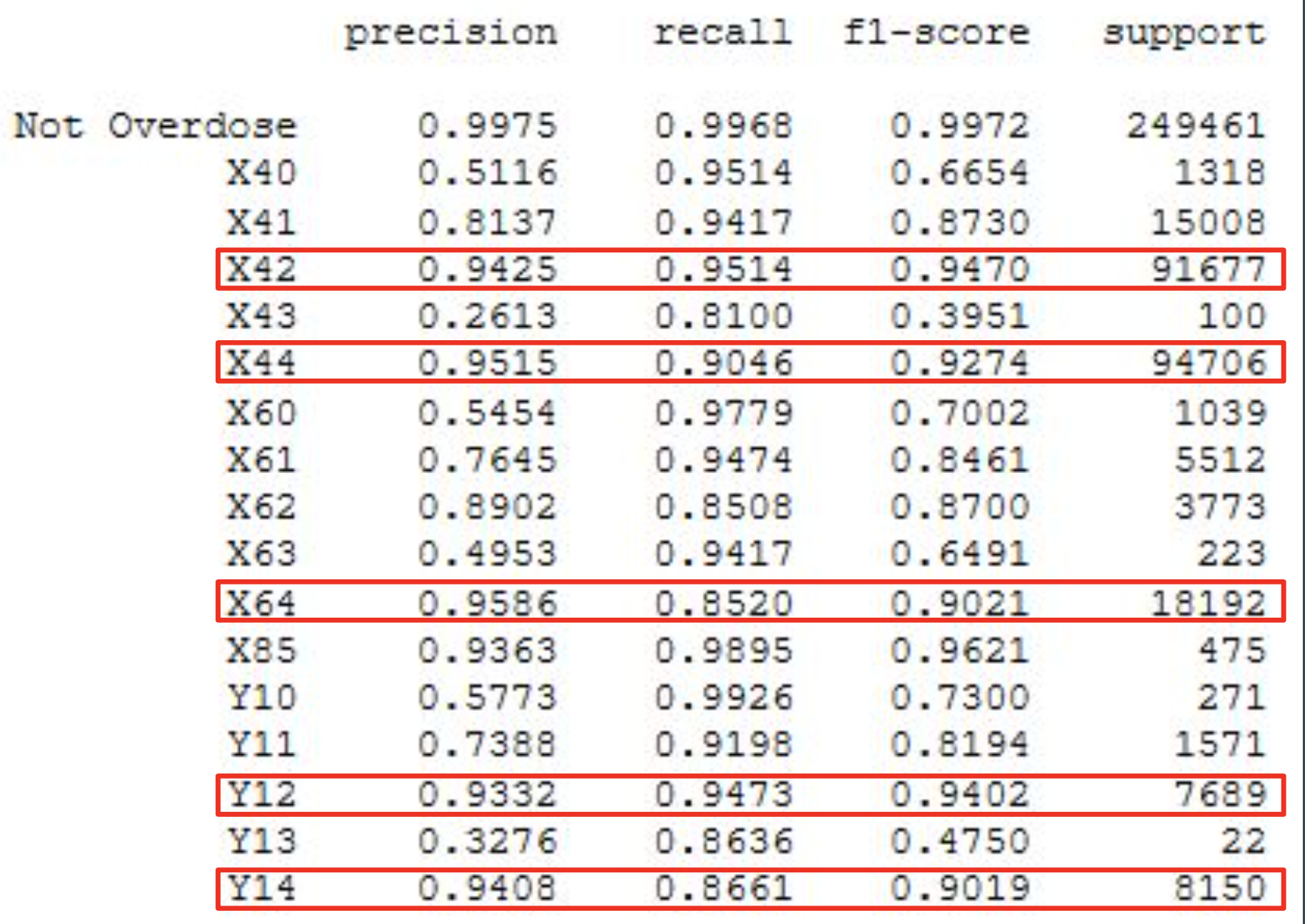

Models with the best performance in each classifier were combined together to identify records with a status of drug overdose and based on the predicted intent and mechanism categories, assign an ICD-10 code from the subset X40-44, X60-64, X85, and Y10-Y14. The mapping of intent and mechanism categories to individual ICD-10 codes are provided within a lookup table for the final assignment of ICD code.

Data Preprocessing

The following pre-processing steps were applied to mortality and literal text data files:

-

Add flag variables for drug overdose status, intent, mechanism

-

Remove rows with missing or uninformative literal text

-

Standardize text - All uppercase, stripped punctuation and numbers

-

Concatenate text fields and convert to document term matrix (i.e. bag of words)

Sampling

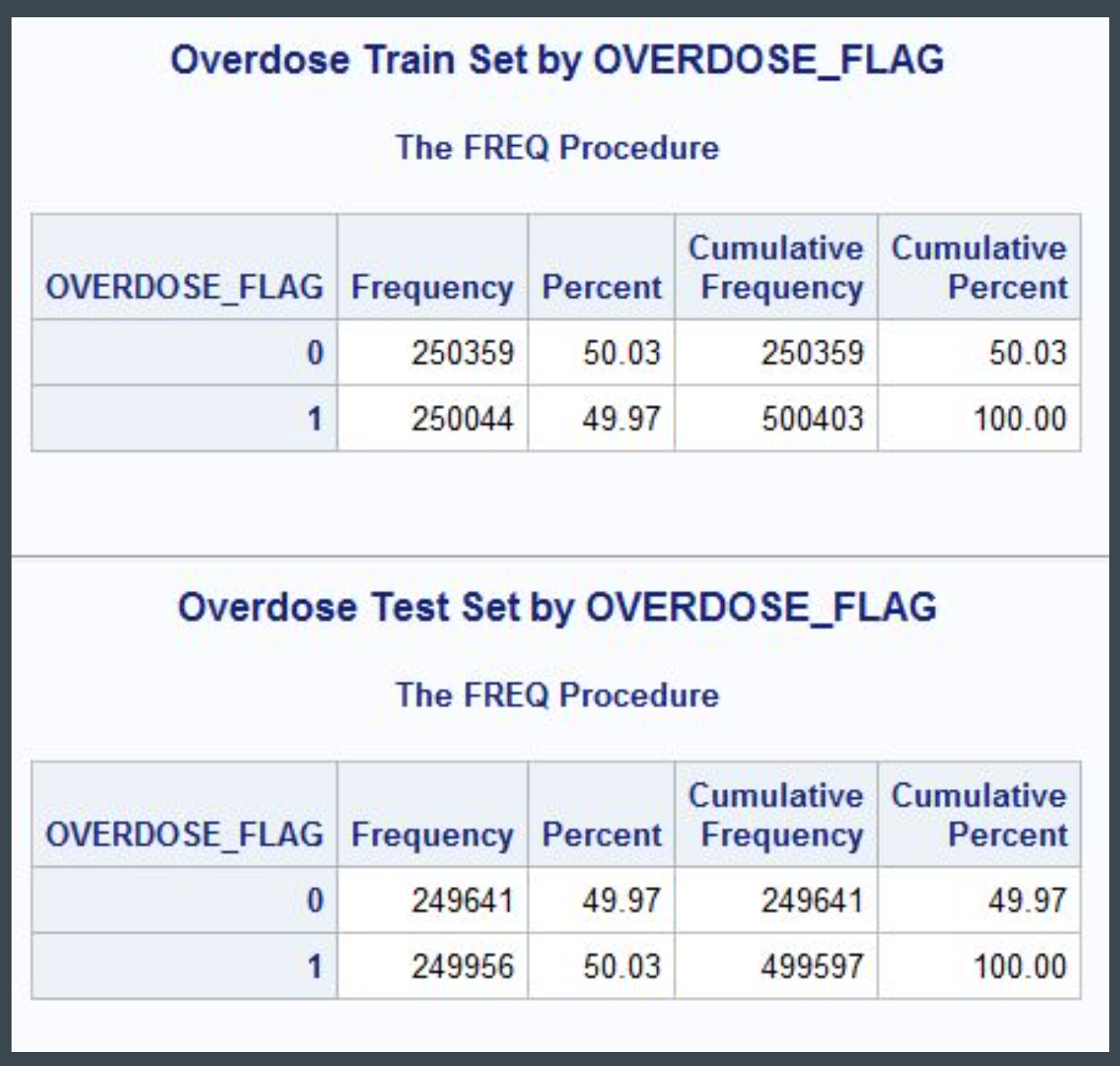

The main limitation of the mortality file is the significant class imbalance between overdose (~500,000 records) and non-overdose (32 million records). To account for this imbalance, a stratified sample of 500,000 overdose and non-overdose records was taken, using simple random sampling without replacement. The records were then divided evenly into training and test sets. Due to class imbalance among specific ICD codes, under-represented classes were oversampled.

Experimental Design

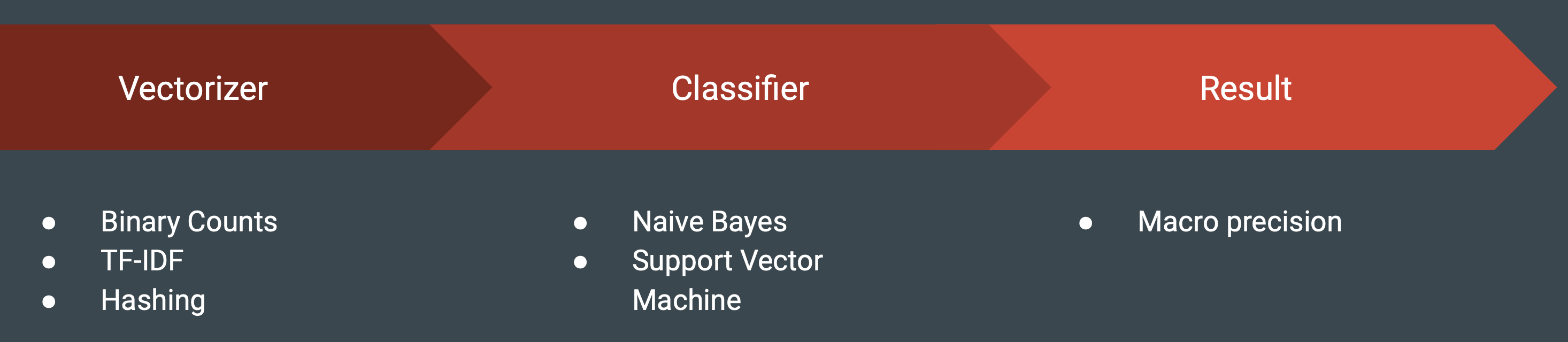

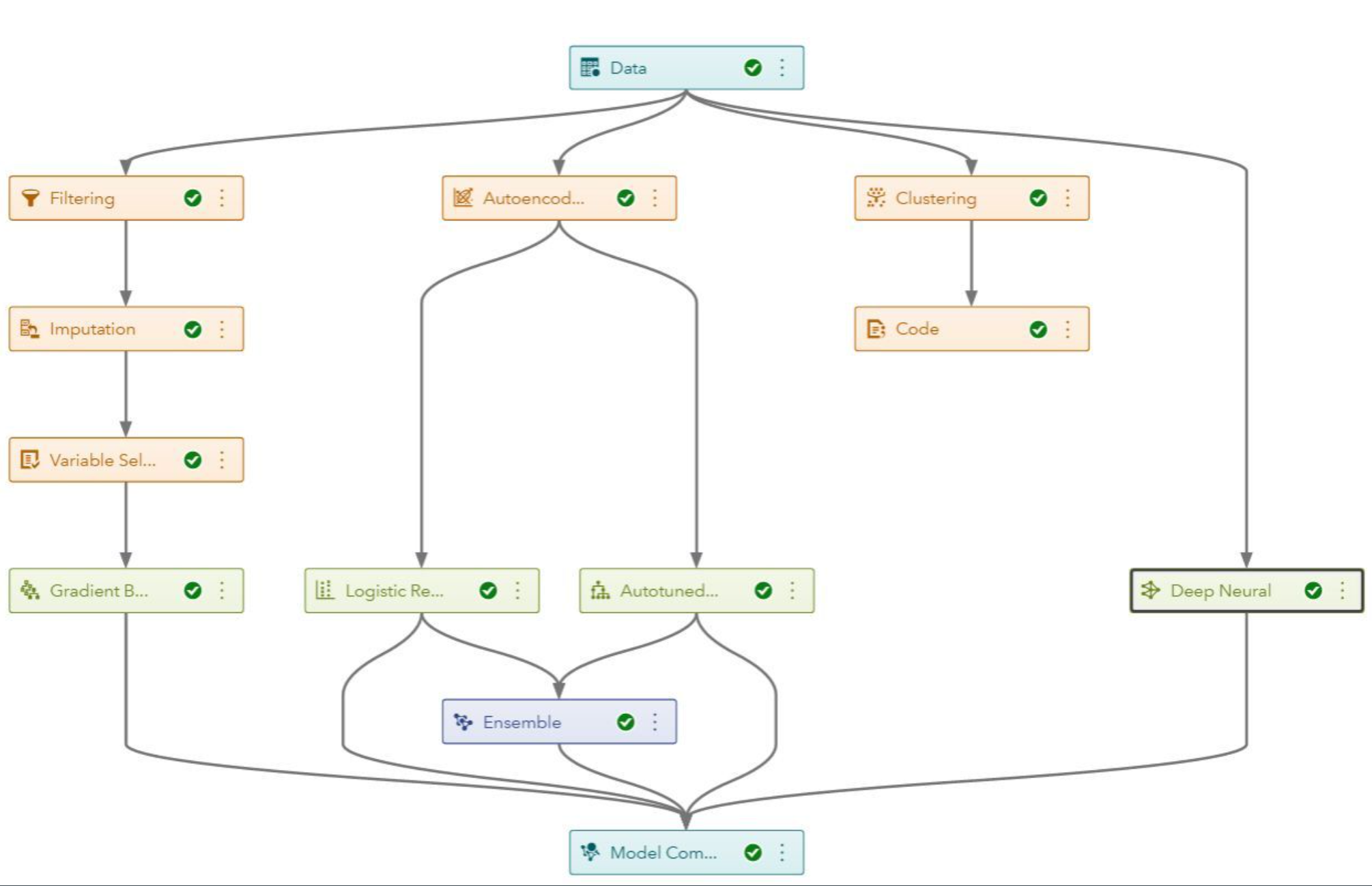

The Scikit-Learn package of Python was used to develop a machine learning pipeline for this project. The pipeline can be broken into three main categories:

-

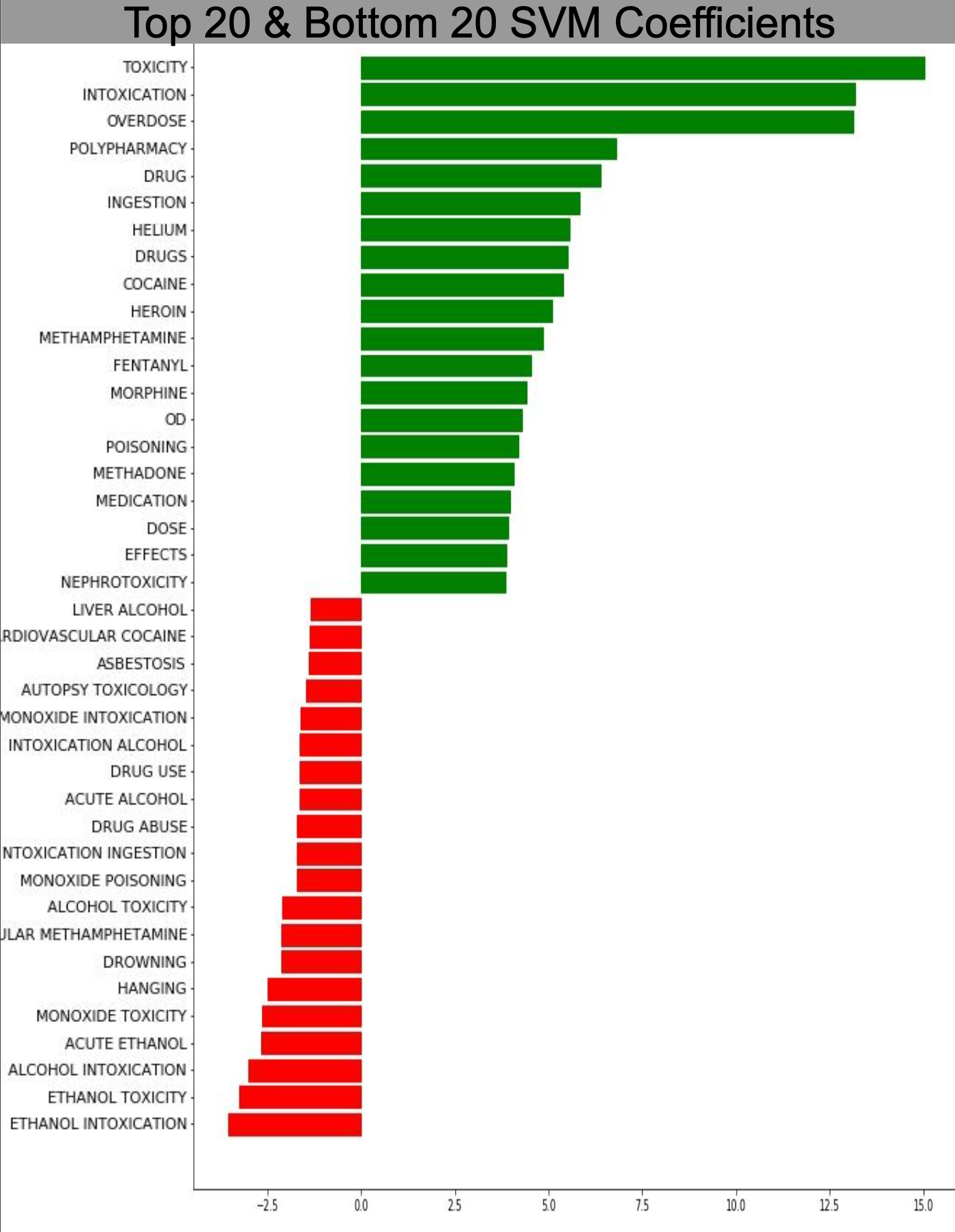

Vectorizer - This initial step transforms the pre-processed data into a term-document matrix using a chosen vectorizer. Values could take on binary counts to indicate the presence or absence of a word in a given record, TF-IDF to indicate the relative importance of a word in a record relative to the entire corpus/dataset, or specialized hashing vectorizers which run the terms through a hashing function and indicate presence or absence of a hashed word. The hashing vectorizer removes the need for stored vocabularies saving storage, but can be problematic as multiple words resolve to the same value when passed through the hashing function. This also hinders downstream interpretability of the models. For example, examining coefficients of an SVM model may indicate which terms from the source vocabulary have the most predictive power for overdose or non-overdose status, shown in the below figure.

-

Classifier - Methods such as Naive Bayes (NB) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) have been found to be successful for classifying records containing drug mentions with involvement (Lipphardt, 2018). Using the appropriate features, these linear classifiers have often been shown to perform on par with state-of-the-art algorithms in text classification (Wang & Manning, 2012). These are the primary algorithms that were considered within the scope of this project. Results from Wang and Manning (2012) also show that in general Multinomial Naive Bayes outperforms Multivariate Bernoulli Naive Bayes and that binarized values are better than standard counts (pg. 90). Based on these findings the Multinomial Naive Bayes with binarized values are chosen as the preferred model for Naive Bayes classifiers. SVM models are implemented with a linear kernel based on the fact that text classification problems are often found to be linearly separable given the high dimensionality of the feature space.

-

Result - To determine optimal hyperparameters for machine learning models, a grid search in Scikit-Learn was used to test combinations of parameters, measuring performance using three fold cross validation. Grid search was configured to select optimal parameters based off a precision macro-average, which computes the unweighted mean precision among all class labels. Once optimal hyperparameters are chosen, model predictions are obtained on the test set to determine final precision scores.

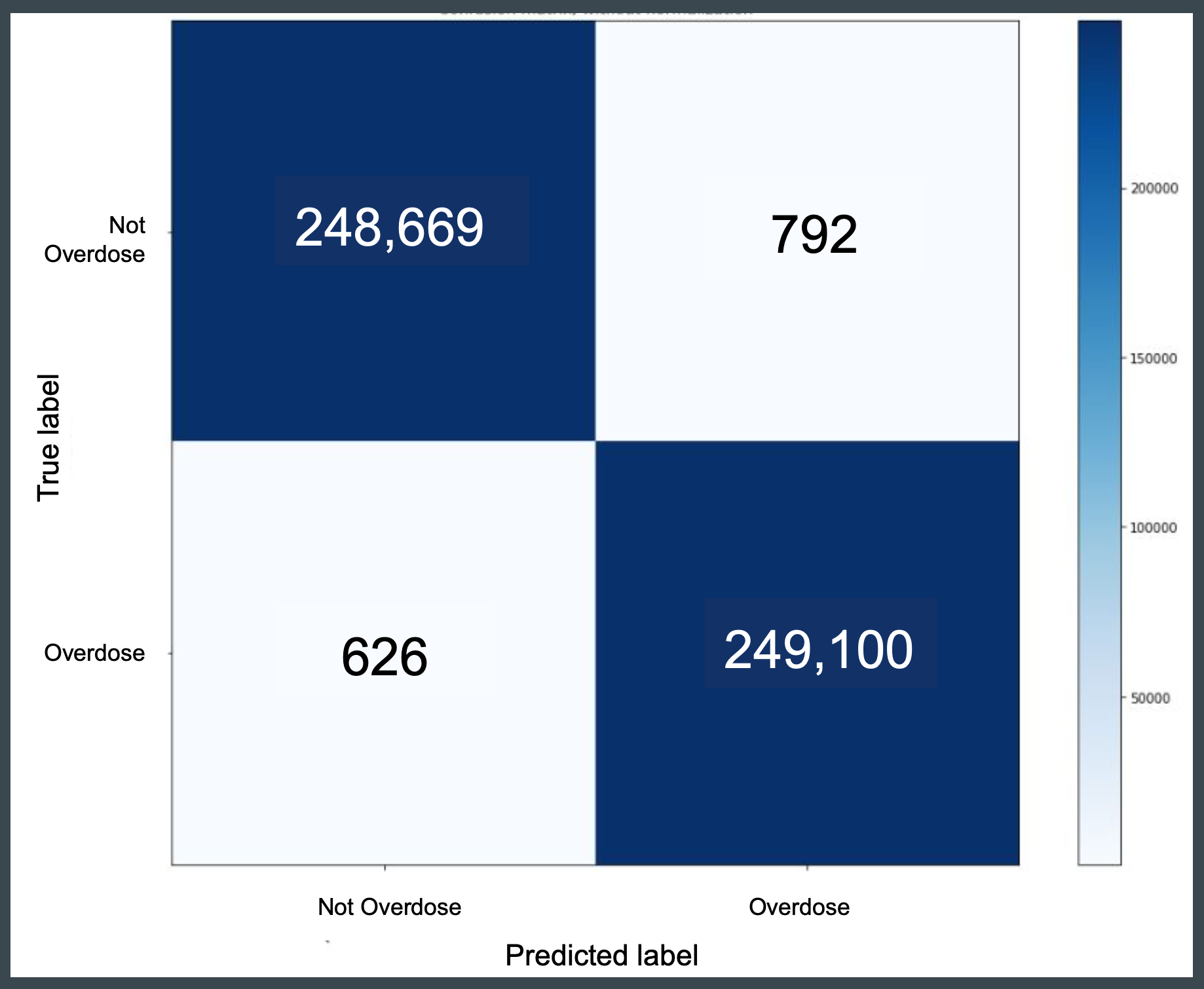

Overdose Status

The performance of the model developed in this capstone project is compared to the baseline detailed in work by Trinidad, Warner, Bastian, Minino & Hedegaard (2016). Compared to the baseline model, the capstone models based on machine learning SVM classifiers outperform with a precision score of 99.7 percent.

- Baseline Model

- Exact Term Matching

- 2013 data year

- 2,000 records

- Precision: 95.8%

- Capstone Model

- SVM Classifier

- 2005-2017 data years

- 499,187 records

- Precision: 99.7%

These results support a potential use case for developing near real-time provisional counts of drug overdose deaths, not taking into account individual ICD-10 codes or drug clases. It should be noted that this model does not consider or determine multiple cause codes, which are an important component of the final mortality file. However, given that more than two thirds of drug overdose records must be coded manually, this method would provide a rapid way of flagging records for manual review.

Organizations working primarily in SAS may conder that Visual Data Mining and Machine Learning product within the SAS Viya platform to develop these machine learning pipelines. Supported CAS libraries or APIs allow integration of Python and R models into the data pipeline.

Individual ICD-10 Codes

Using the best models or heuristics for overdose status, intent, and mechanism, ICD-10 codes were obtained using the sample of 499,187 records split evenly between overdose and non-overdose deaths.

Classification on individual ICD-10 codes resulted in a precision weighted macro-average of 0.9627, with precision scores for individual codes ranging from 0.2613 to 0.9586. Recall weighted macro-average was 0.9590, with recall scores for individual classes ranging from 0.81 to 0.9926.

From these results it can be observed that the model exhibits good sensitivity and typically predicts class labels accurately for more than 95 percent of the records it is passed. However, given the heavy class imbalance, precision scores for ICD-10 codes with little support suffer when the model assigns false positives.

- Weighted macro avg.

- Precision: 96.2%

- Recall: 95.9%

- Unweighted macro avg.

- Precision: 74.0%

- Recall: 92.4%

Future work for predictive models may focus on improvements towards mechanism classifier performance, which exhibits low support for select ICD-10 codesw. Improvements might be gained through additional pre-processing - reducing the number of terms considered - and modern techniques such as deep neural networks (e.g. RNN, LSTM) which take advantage of context provided by word order.

For the purposes of this capstone project, techniques or toolsets were constrained by the amount of training data and availablity of processing power or toolsets on NCHS’ consolidated statistical platform. As additional processing power and toolsets become on the platform, deep learning models may be incorporated.

Secondary Objective: Extract Known and Novel Drug Mentions

As discussed, prior work by Trinidad et al. (2016) has focused on the use of SAS programs to identify drug mentions with involvement (DMI) within literal text fields via exact matches and regular expressions.

Trinidad et al. (2016) note:

The importance of creating comprehensive lists to be used by the DMI programs cannot be overstated. The DMI programs are a series of steps that identify drug mentions, descriptors of those drug mentions, and other contextual information. Each step of the processing of literal text requires lists: search terms, descriptors, joining phrases, or contextual phrases. Incomplete lists used by the DMI programs may result in failure in any of the processing steps, which would result in a failure to associate drug mentions with the appropriate contextual information. (p. 13)

Although the programs are designed to obtain a high level of agreement with ICD-10 codes assigned through manual review, the process of developing precompiled lists is extremely time intensive and may miss drugs rarely involved in drug overdose deaths as well as uncommon abbreviations or misspellings. Future work is focused on identifying not only known drug mentions, but emerging trends in drug mortality such as the introduction of new fentanyl analogs. In order to improve the quality of reporting for drug overdose deaths, it is desirable to develop a model that can automatically extract both known and novel drug mentions.

One method considered was to expand the lists maintained for the current NCHS DMI programs using more comprehensive vocabularies such as the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS), which provides access to a metathesaurus containing terms across multiple standards such as ICD-10, MeSH, RxNorm, and SNOMED. This method would potentially miss acronyms, abbreviations, and misspellings. Research from Tolentino et al. has focused on incorporating numerous algorithms to identify and correct these issues in a pre-processing step, but result in low sensitivity and precision (2007). The system also has the potential to miss newly emerging drugs or slang terms.

An alternative method using unsupervised machine learning comes from research by Simpson, Adams, Brugman, and Conners (2018), which explored the use of word embeddings to detect novel and emerging drug mentions in social media. The original paper explores the use of the word2vec algorithm to identify novel drug mentions for the target substance ‘marijuana’ in social media by querying the model for top terms according to cosine similarity. Candidate terms were then manually reviewed to verify novel mentions. A semi-automated version of this approach may be used to identify known drug mentions by calculating cosine similarity between each word in a record and one or more selected target words, flagging those words which exceed an optimal threshold value. The fastText algorithm introduced by Bojanowski, Grave, Joulin, and Mikolov (2016) extends word2vec by considering not only individual words, but character n-grams within word boundaries. Word vectors for complete words are constructed by summing the character ngram word vectors together, allowing vectors to be generated for out-of-vocabulary words. This algorithm was also tested within the context of this project to identify potential misspellings or novel drug mentions.

Summary of Word2Vec

A complete review of the word2vec and fastText algorithms are outside the scope of this writeup. For detailed information, see original articles by Mikolov et al (2013) and Bojanowski et al (2017). A brief overview of word2vec is provided below.

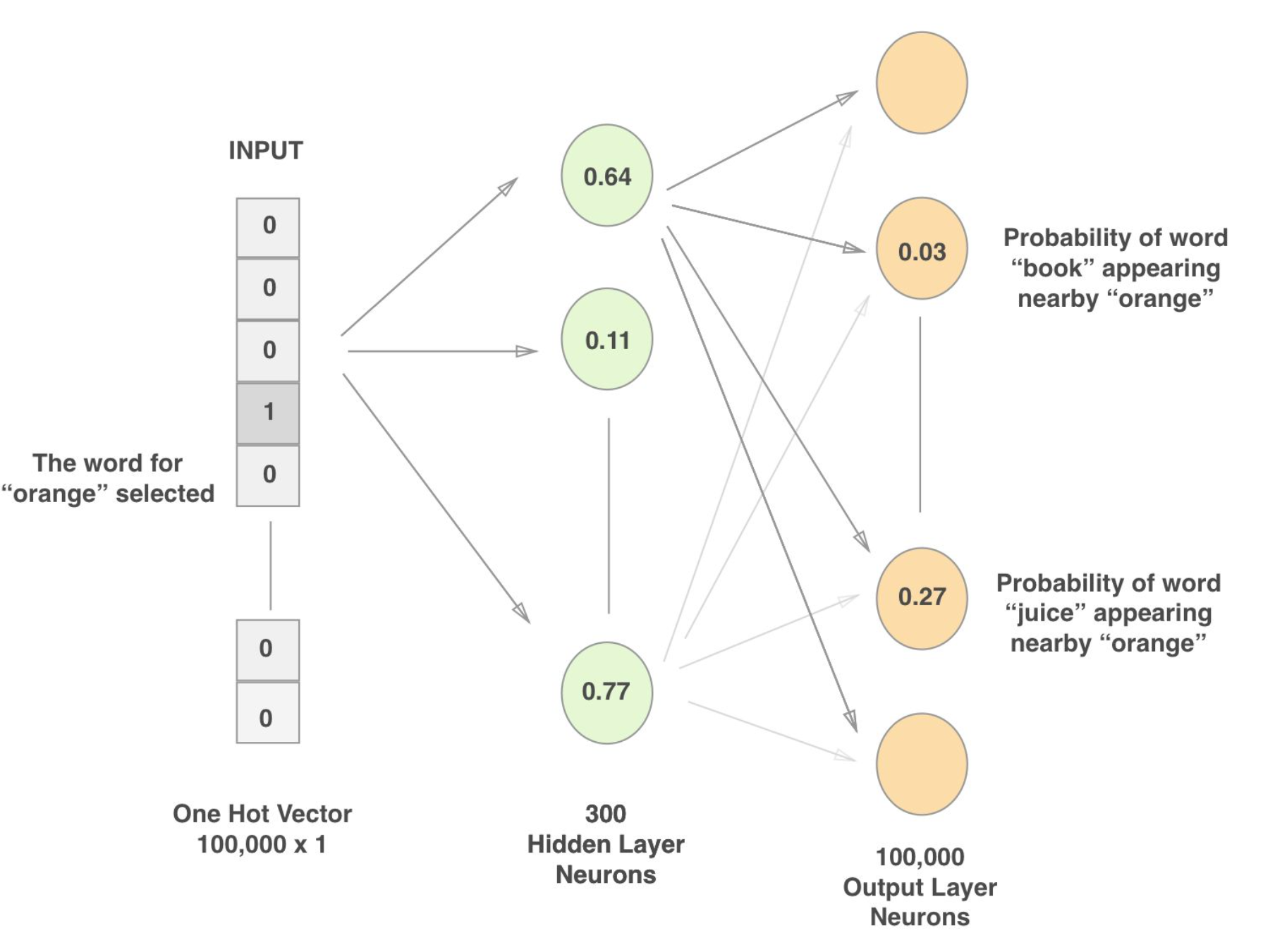

word2vec comes in two flavors, using either a continuous bag of words (CBOW) or a skip-gram approach. The CBOW approach is used within this capstone project.

CBOW trains a neural network model by passing as input a one hot vector for a word that occurs in a given context, passes it through a hidden layer, and attempts to predict the probability of all other words within the vocabulary occurring in the same context/window using a softmax classifier. The network is optimized to minimize the loss in predicting probabilities for context words in the softmax layer. Once this loss is minimized, values are obtained from the hidden layer, also known as the embedding layer, to construct an embedding matrix of word vectors. The resulting word vectors can be used to compare semantic similarity using various distance measures. Cosine similarity is used within this project to compare word similarity.

Data Preprocessing

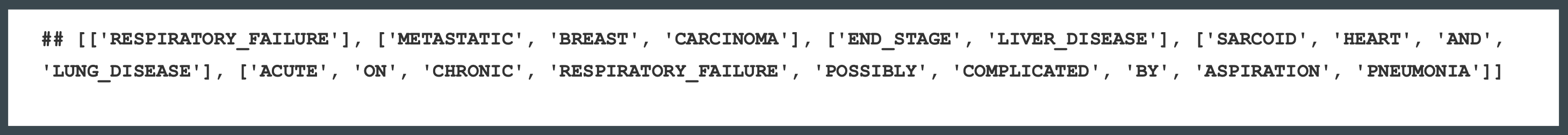

Provisioned data files for 2005 through 2017 were used to build the corpus for word embedding models, using a stratified sample of 500,000 overdose and non-overdose records each. Only literal text fields pertaining to Part I, II, and Box 43 of the standard certificate of death were retained. These fields were then unpivoted and stacked into a single column of lines of text. All lines of text were converted to uppercase.

Using the NLTK Python package, each line was tokenized splitting on non-word characters to convert the corpus to a python list of tokenized sentences (i.e., a list of token lists). The Phrases model of the gensim package was then built using this list to detect common bigrams (i.e., adjacent word pairs) within the corpus. Hyperparameters for the minimum frequency of bigrams and the threshold for forming bigram phrases were initially kept at their defaults of 5 and 10, respectively. Once the phrases model was built, the list of tokenized sentences was passed through the phrases model to replace common pairs of tokens with detected phrases. Performance of models with and without bigrams were evaluated.

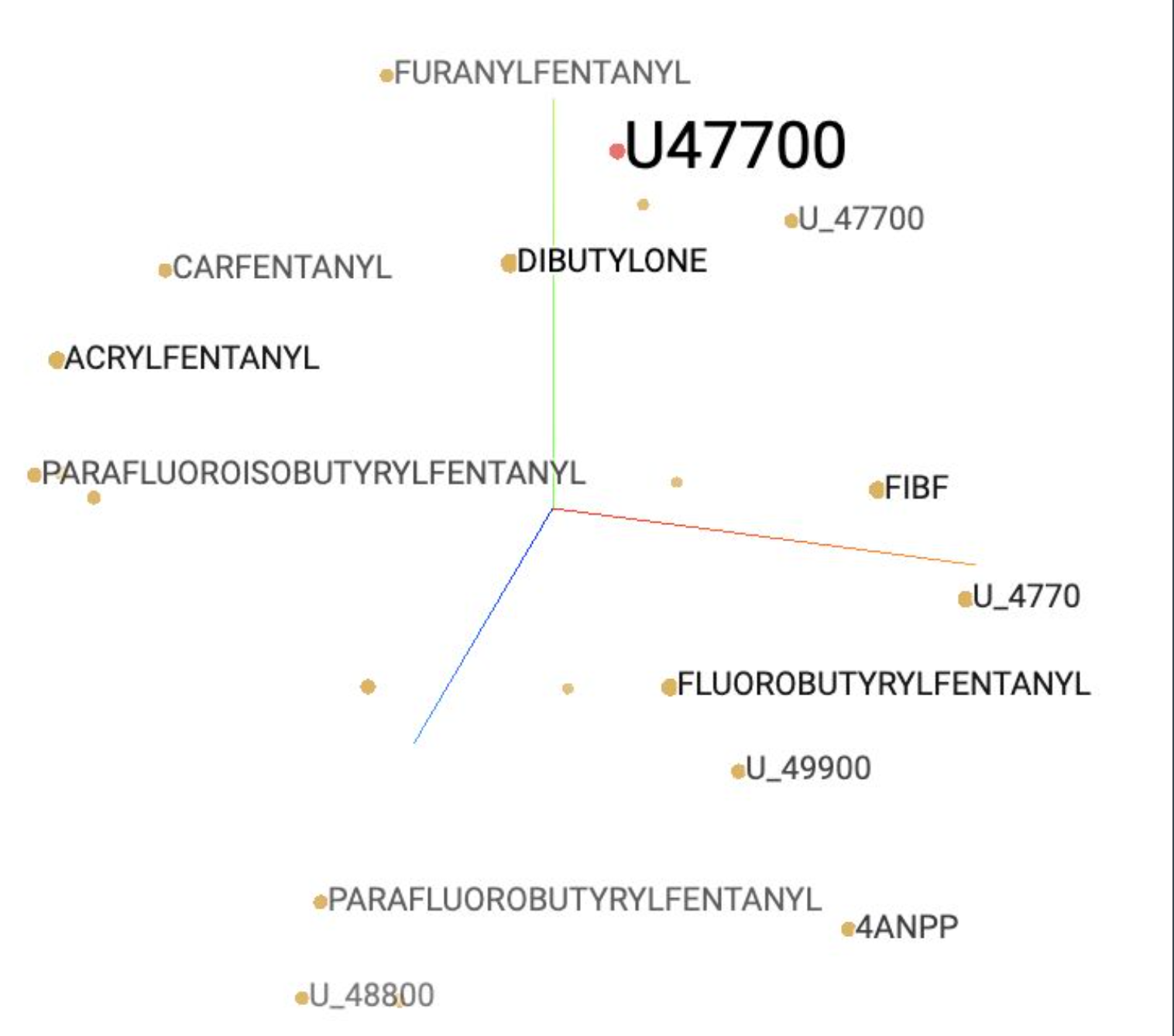

To prevent unimportant numeric values from being included in the word embedding model, regular expressions were used to strip years prior to phrase detection and any remaining numbers following replacement of phrases. This allowed detected phrases such as ‘U_47700’ (a synthetic opioid) and ‘TYPE_2’ (relating to TYPE 2 DIABETES) to be included within the model.

Task 1: Measure Agreement with Historical Records

The first task analyzes NCHS mortality and literal text records for data year 2017 using optimal word vectors to identify target substances based on cosine similarity. Flagged records only consider mentions of the drugs themselves and do not take into consideration contextual information such as degree of certainty (e.g. ‘PROBABLE’, ‘UNKNOWN’) or temporal relationships (e.g. ‘HISTORY’, ‘PAST’, ‘RECENT’, ‘REMOTE’).

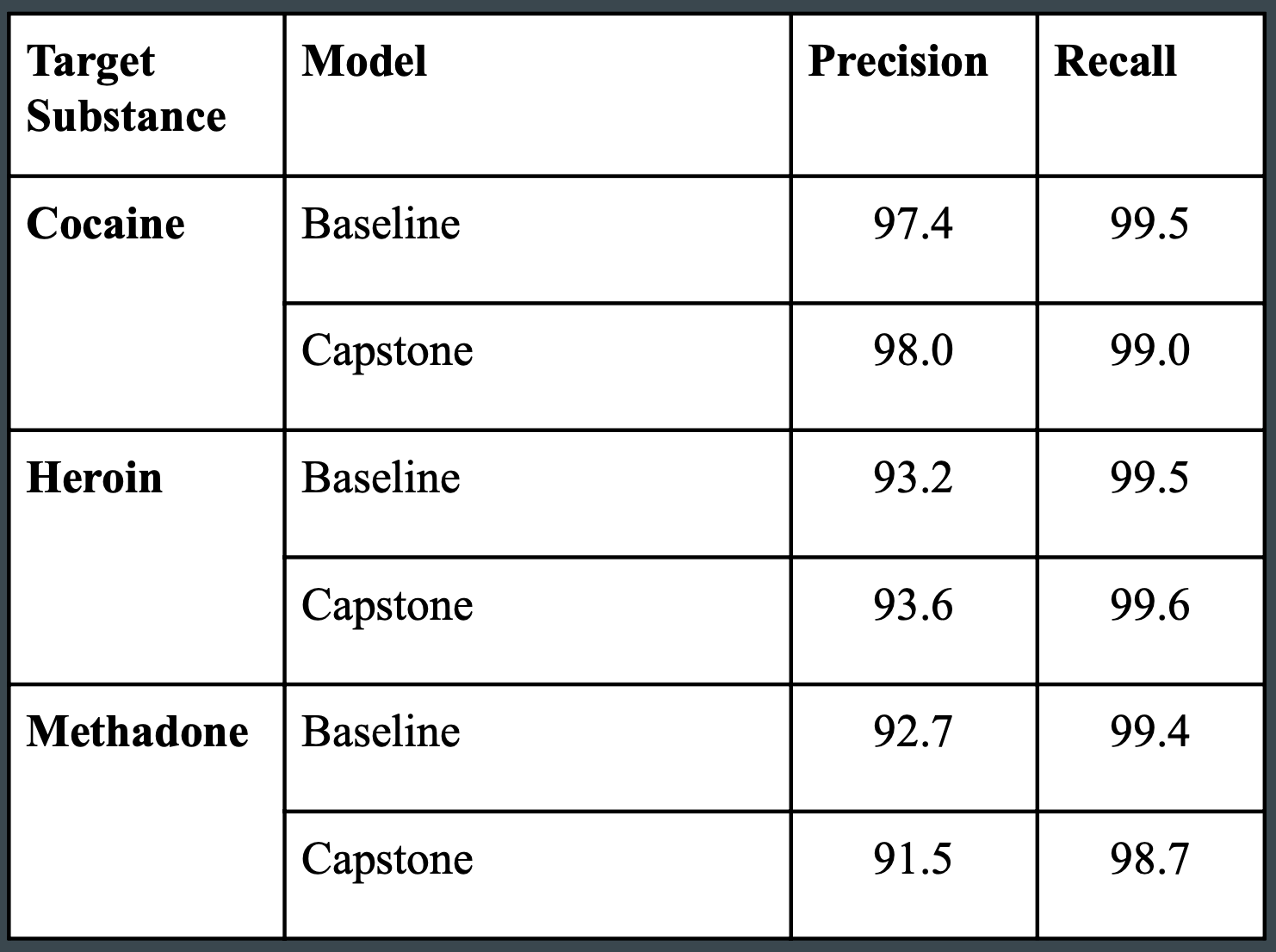

Detailed results of the analysis using word embedding models are provided in the table below and compared with the results of Trinidad et. al (2016) as the baseline.

The first metric calculates precision, which finds the proportion of records with flagged mentions for the target substance that actually had an applicable ICD-10 code. Given that contextual information was ignored in this approach, performance was remarkably similar to the results by Trinidad et. al, resulting in precision scores between 91.5 and 98.0 percent.

The second metric calculates sensitivity or recall, which finds the proportion of records assigned a code for the target substance which were identified. The approach using word embedding models performed on par with the DMI programs, resulting in sensitivity between 98.6 and 99.6 percent.

Given the performance of this approach, it is possible that word embedding models may be designed as a reliable alternative method to identifying known drug mentions, despite the lack of contextual information required to rule out drug mentions without involvement.

Task 2: Search for Novel Drug Terms

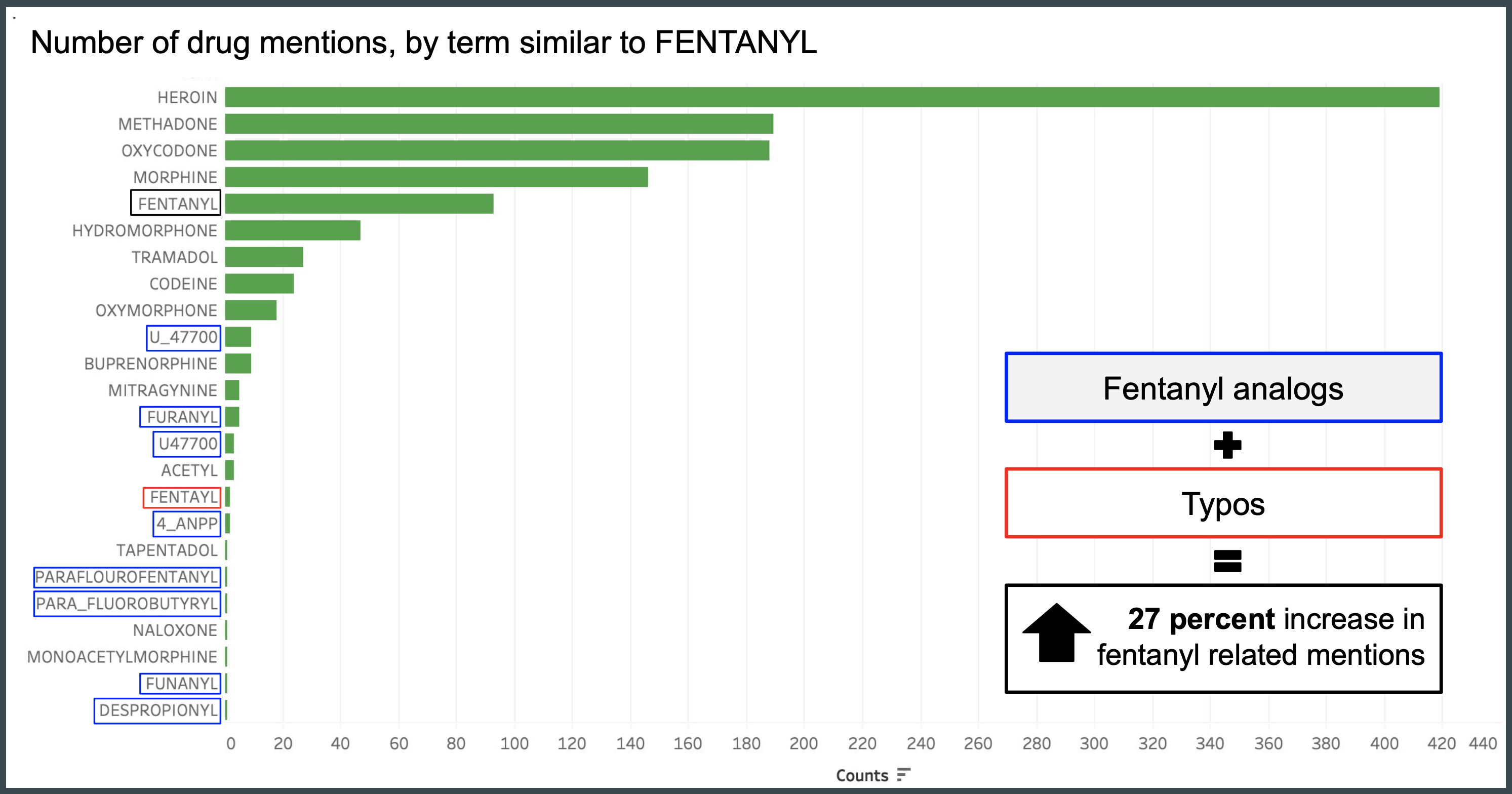

The second task analyzes public records from Washington state for data year 2016 by comparing cosine similarity of each term or phrase to a list of common metabolites, precursors, and analogs used as search terms for identifying fentanyl.

A listing of opioid and non-opioid terms were flagged using the word embedding models. Raw counts of the drug mentions were used to measure the rarity of a term within the dataset. Approximately 78 terms were identified in the dataset based on cosine similarity. 24 of these terms were opioid related and 54 terms were non-opioid terms. Drug terms comprised 72 of the 78 identified terms with non-drug terms including INTOXICATION, NEUROMYELITIS, PHLEGMASIA, NOR, SUNDAY, and VINYL.

Top opioid terms based on counts include known drug mentions such as HEROIN, METHADONE, and FENTANYL. Drugs with smaller counts include infrequently cited metabolites and their typos (e.g. PARAFLOUROFENTANYL, FUNANYL) as well as lesser known illicit drugs (U_47700, U47700, 4_ANPP) not included on the expert list used by Trinidad et. al (2016). The addition of verified typos and fentanyl analogs resulted in a 27 percent increase in fentanyl related mentions.

Using this approach, a corpus of approximately 22,000 unique terms were narrowed down using automated tools to 78 terms requiring manual review and using raw counts provided a mechanism to quickly identify novel mentions. The limitations of this method are that word vectors are dependent on the size and quality of the training dataset and that false positives may be generated. Therefore, these techniques would be best served as a complementary method to existing search term list approaches to identify new candidate terms. This technique could easily be applied to the most recently available year of mortality and literal text data to identify terms similar to fentanyl.

Summary

References

Aggarwal, C.C., & Zhai, C.X. (2012). A survey of text classification algorithms. In Mining text data (pp 163-222). Boston, MA: Springer.

Bojanowski, P., Grave, E., Joulin, A., & Mikolov, T. (2016). Enriching word vectors with subword information. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/pdf/1607.04606.pdf

Cameron, H.M., & McGoogan, E. (1981). A prospective study of 1152 hospital autopsies: I. Inaccuracies in death certification. The journal of pathology, 133(4). doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1711330402

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018). Understanding the epidemic. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

Hedegaard, H., Miniño, A.M., Warner, M. (2018). Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, 329. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db329-h.pdf

Joulin, A., Grave, E., Bojanowski, P., & Mikolov, T. (2016). Bag of tricks for ef icient text classification. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/pdf/1607.01759.pdf

Lipphardt, A. (2018). Using cause-of-death literal text from the death certificate for classification. Retrieved from https://github.com/alipphardt/dmi-deaths-classification.

Mikolov, T., Chen, K., Corrado, G., & Dean, J. (2013). Ef icient estimation of word representations in vector space. Retrieved from: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1301.3781.pdf

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). (2018). Release of 2016 multiple cause-of-death data file. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/Multiple_Cause_Record_Layout_2016.pdf

Quoc, V.L., & Mikolov, T. (2014). Distributed representations of sentences and documents. Retrieved from: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1405.4053.pdf

Simpson, S.S., Adams, N., Brugman, C.M., & Conners, T.J. (2018). Detecting novel and emerging drug terms using natural language processing: A social media corpus study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 4(1).

Spencer, M.R., Warner, M., Bastian, B.A., Trinidad, J.P., & Hedegaard, H. (2019) Drug overdose deaths involving fentanyl, 2011–2016. National vital statistics reports, 68(3). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_03-508.pdf

Trinidad, J.P., Warner M., Bastian, B.A., Minino, A.M., & Hedegaard H. (2016). Using literal text from the death certificate to enhance mortality statistics: Characterizing drug involvement in deaths. National vital statistics reports, 65(9). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Tolentino, H.D., Matters, M. D., Walop, W., Law, B., Tong, W., Liu, F., Fontelo, P., Kohl, K., & Payne, D.C. (2007). A UMLS-based spell checker for natural language processing in vaccine safety. BMC medical informatics and decision making, 7, 3. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-7-3

Wang, S., & Manning, C.D. (2012). Baselines and bigrams: Simple, good sentiment and topic classification. In Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 90–94). Retrieved from https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/P12-2018