Classifying Drug Mention with Involvement (DMI) Deaths

Project, Data, and General Approach

Problem

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) works in partnership with state and local governments to collect, analyze, and disseminate data on vital statistics, including birth and death events. This data is used to monitor trends of public health importance such as the ongoing opioid crisis. The most current data from 2016 indicates that deaths from opioids were 5 times higher than in 1999, and provisional estimates indicate that these numbers are continuing to rise.

Mortality data is currently coded using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), which is used to identify underlying and contributory causes of death. Coding for drug involved deaths are currently problematic for a number of reasons including:

- Initial coding of ICD-10 classifications - NCHS uses automated programs to assign 1 underlying cause of death and up to 20 multiple causes of death. In general, the program rejects about one fifth of death records which must be reviewed and coded by trained nosologists. However, for deaths with an underlying cause of drug overdose, about two-thirds of records are manually coded.

- Limited codes for specific drugs - ICD-10 is limited in capturing drug-involved mortality as it only contains a few codes pertaining to specific drugs (e.g. heroin, methadone, cocaine) and these codes are only applied in specific circumstances. Most drugs are coded using broad categories, making it difficult to monitor trends in specific drugs that are not already uniquely classified by ICD-10.

Recent efforts have been placed on developing programs to extract drug mentions from literal text fields of the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death. These fields include:

- The chain of events leading to death (from Part I)

- Other siginificant conditions that contributed to cause of death (from Part II)

- How the injury occurred (in the case of deaths due to injuries [from Box 43])

Programs developed rely on exact pattern matching and significant collaboration between NCHS and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop search terms for identified drug mentions, descriptors (e.g., illicit, prescription/RX), and contextual phrases (e.g., Ingested, History/HX of Abuse). Use of literal text analysis provides an opportunity for an enhanced understanding of the national picture of drug involvement in deaths in the United States, but is also problematic in the time involved to develop and maintain programs based on exact pattern matching.

Data

NCHS performs literal text analysis using final death files from NCHS’ National Vital Statistics System linked to literal text data. This data is collected from state and local vital records offices and cleaned and coded in preparation for analysis. Due to privacy and confidentiality concerns, literal text data files are unavailable outside of the CDC/NCHS secure data platform.

However, Washington State’s Department of Health provides both annual files and literal text files for purchase, which are largely similar to the information collected by NCHS.

For the purpose of this analysis, the most recent 2 years of data (i.e., 2015 and 2016 annual files and literal text files) were purchased for use. Each dataset was provided as a CSV dataset and has been linked through common attributes such as year and death certificate number. Each dataset includes records for approximately 50,000 deaths in the State of Washington.

Note: Original annual and literal text files have been excluded from the GitHub repo. However, preprocessed data with the combined literal text fields are made available as a CSV.

The annual files, have approximately 133 fields, which are described by the File Layout [XLSX] on the Washington Department of Health website.

Of interest in the annual file is the certificate number, used for linking, and the ICD-10 code for underlying cause of death and up to 20 multiple causes of death.

The literal text files, have the following layout:

- ‘State File Number’,

- ‘Cause of Death - Line A’

- ‘Cause of Death - Line B’

- ‘Cause of Death - Line C’,

- ‘Cause of Death - Line D’

- ‘Interval Time - Line A’,

- ‘Interval Time - Line B’

- ‘Interval Time - Line C’,

- ‘Interval Time - Line D’

- ‘Other Significant Conditions’,

- ‘How Injury Occurred’

- ‘Place of Injury’

From the linked file, a derived feature will be created as a label to classify a record as a drug mentioned with involvement (DMI) death or not. Death records coded with an underlying cause of death ICD code (i.e., X40–X44, X60–X64, X85, or Y10–Y14) will be marked as a DMI death. Additionally, remaining records with flagged drug mentions will be reviewed manually and classified as a DMI death.

Preprocessed data includes CSV with literal text field and DMI target and is named: literal-text.csv

The final dataset created within the experiments will consist of a matrix of binary term-frequencies and a class label called DMI. The full term-frequency matrix is not stored due to large file size (12 GB) depending on hyper-parameters used by CountVectorizer.

Objectives

This project will address whether machine learning techniques can be used to train a classifier to predict with high precision and specificity whether a death record is a drug mention with involvement (DMI) death or not.

- Precision, also known as positive predictive value, is the proportion of records predicted to be in the positive class (in this case a DMI death) that were correctly classified (TP/TP+FP).

- Specificity, also known as true negative rate, is the proportion of records in the negative class that were accurately predicted (TN/TN+FP).

We wish to maximize these two metrics as the problem demands that we find a solution that accurately determines whether a record is in the positive class (DMI death) or not and reduces or avoids instances of false positives. Current programs within NCHS that rely on exact pattern matching achieve a precision score of 95.8 percent on the DMI class. The objective of this project is to find a solution that exceeds this baseline.

The linked dataset will be converted to a term-frequency matrix that stores each word/term as a 1 if the term is used in a given record and 0 if it is not. As discussed previously, a derived feature will be created using existing ICD codes and flagged drug mentions to identify whether a record is a DMI death or not.

The intended benefits of the described solution are as follows:

- Improve identification of DMI deaths, potentially reducing the amount of manual reviews for drug overdose deaths.

- Develop a generalized solution that removes the need for development of exhaustive lists of search terms, descriptors, and contextual phrases.

Once a classifier is obtained to more accurately identify DMI deaths, we can extract drug mentions from those records to better track trends of drug involvement in deaths.

Approach

Our approach will use the following machine learning techniques:

- Bag-of-words/Term Frequencies Model (CountVectorizer in scikit-learn) - The dataset will be transformed into a matrix of binary term-frequencies (0 or 1), which is common in text mining tasks. Words that appear more than 3 times will be included and combinations of individual words and adjacent word pairings will be tested.

- Support Vector Machine (SVC in scikit-learn) - This algorithm is popular in text classification tasks and is suitable for datasets that are not too large. Since our task is a binary classification, our solution only requires a single SVM. Our dataset consists of 100,000 records, but it is expected to be a fraction of that once we obtain our class labels and balance the dataset. SVMs are popular in text classification as they scale well for high dimensionality data and can perform with high accuracy and stability on both linear and nonlinear problems.

- Latent Semantic Analysis (TruncatedSVD in scikit-learn) - Given that the creation of a term-frequency matrix will likely result in thousands of features, dimensionality reduction may prove useful in improving training speed and predictive power of the classifier, particularly if pairs of terms are heavily correlated. Note that we are only applying this to SVM as Naive Bayes expects discrete data.

- Naive Bayes (Bernoulli Naive Bayes in scikit-learn)- Despite the assumption of independence, Naive Bayes has been found to work well in text classification. It works well for this scenario as the algorithm is quick to train and scales well on high dimensionality data. Because our term-frequency matrix will only consist of 0s and 1s, we have discrete values, which Naive Bayes works well on.

Pre-processing

Data Cleaning

- 2015 and 2016 documents used different names for columns. Renaming was done to conform to standard column labels. This would facilitate concatenation and merging of the datasets.

- The following fields were retained:

- State file number (i.e., certificate number)

- Underlying Cause-of-Death (single cause)

- Multiple Cause-of-Death (up to 20 causes)

- The chain of events leading to death (from Part I)

- Cause-of-Death Line A

- Cause-of-Death Line B

- Cause-of-Death Line C

- Cause-of-Death Line D

- Other siginificant conditions that contributed to cause of death (from Part II)

- Other Significant Conditions

- How the injury occurred (in the case of deaths due to injuries [from Box 43])

- How the Injury Occurred

- Irrelevant fields were dropped from the dataset. These include but are not limited to:

- Interval Time - Line (A/B/C/D)

- COD-DUE-TO-(B/C/D) - Further inspection shows only one record in 2015 using this field

- Injury Place

- A left join between the annual and literal text files was performed to create a single dataset with DMI targets and literal text fields. Literal text fields including Part I cause of death variables, How Injury Occurred, and Other Significant Conditions were combined into a single literal text field.

- Rows with missing values for the literal text and DMI fields were removed.

- Literal text field was stripped of punctuation and stop words using NLTK module, as well as removing numbers.

- Standardization was not performed as term-frequency matrix will consist of discrete 0’s or 1’s in order to use classifiers such as Naive Bayes.

Feature Engineering

- Year field was added to 2015-2016 annual and literal text files for the purpose of linkage between these datasets

- DMI field was added as a target label. Deaths with an underlying or multiple cause of death for the following ICD codes were flagged as a DMI death: X40–X44, X60–X64, X85, or Y10–Y14. Following pre-processing, the following counts for DMI were obtained:

- DMI (1) - 2498

- Not DMI (0) - 109407

- The literal-text field was converted to a term-frequency matrix using scikit-learn’s CountVectorizer module. Model was created specifying binary frequencies (0 or 1) and a minimum frequency of 5 in the dataset to select a feature. This term frequency matrix was pickled and written out to a file for the next phase of the project, which will combine into a a single data frame with the DMI targets. The python notebook preprocessing.ipynb includes an example of this transformation. This data frame itself was too large to pickle/write to a file (11 GB).

Experimental Plan

Four machine learning techniques from scikit-learn will be utilized in this experiment: CountVectorizer, Latent Semantic Analysis, Naïve Bayes, and Support Vector Machine.

The first step will be to fit the literal text dataset using CountVectorizer to convert the single literal text field into a bag-of-words or term frequencies model with binary frequencies. The results of this dataset will then be included in one of three pipelines:

- Fit to a Naïve Bayes classifier.

- Fit to a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier without dimensionality reduction.

- Perform dimensionality reduction using Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) and fit to a SVM classifier.

Note: PCA was originally planned as the means for dimensionality reduction in this project. However, scikit-learn’s implementation cannot work with the sparse datasets produced by CountVectorizer. Therefore, LSA was used in a similar manner to reduce dimensions while retaining 85-95 percent of explained variance in the dataset.

The workflow will be managed using scikit-learn’s grid search and pipeline constructs. Grid search allows you to set up a parameter grid for each machine learning technique you plan to use and will test every combination within the parameter grid to find an optimal configuration based on your chosen scoring metric. In this experiment, we will use 10-fold cross validation using precision as our scoring metric in the grid search. The pipeline construct allows you to chain together multiple machine learning techniques in scikit-learn while performing the grid search.

Below we detail the combination of parameters that will be supplied to the parameter grids in the initial grid search. Additional parameters may be added as needed.

Based on three pipelines, we will have 35 combinations of parameters: 16 combinations for Naïve Bayes, 16 for SVM, and 3 for SVM without dimensionality. Grid search will perform 10-fold cross validation and select the best parameters based on average precision score.

Prior to running the grid search, the data will be balanced, under-sampling the over-represented class (Non-DMI) to balance the two classes. This is particularly important as the class ratio before under-sampling is roughly 50 to 1. The dataset will then be split into training and test sets using a 75:25 split given the relatively small dataset size once balanced. The portion of the data set aside for training will be passed to the grid search, while the remaining data will be used for final testing and scored on precision and specificity for the DMI class.

The process for these experiments are shown in the provided experiments.ipynb Jupyter notebook. Results of the grid search are in the results folder as a CSV file.

ML Technique #1: Bag-of-Words/Term Frequencies Model (CountVectorizer in scikit-learn)

The bag-of-words model is a common representation for text classification tasks which represents each record as a bag or collection of words - pulled from all records/documents in the dataset - and their frequencies within that particular record. No consideration is given to order, and so the model may be extended to include N-grams which contain groups of N adjacent words.

| Combination | lowercase | binary | min_df | ngram_range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | False | True | 3 | (1,1) |

| 2 | False | True | 3 | (1,2) |

| 3 | False | True | 5 | (1,1) |

| 4 | False | True | 5 | (1,2) |

Each combination of parameters will disable conversion to lower-case, since the dataset is already converted to all uppercase, and binary will be set to True, which will set term frequencies to either 0 or 1, giving us the flexibility to use popular ML techniques such as Naive Bayes which requires discrete data.

The min_df parameter specifies the minimum number of times a word must appear within the dataset for it to be included in the vocabulary for the bag of words model. Three and five are chosen to rule out the potential for typos and misspellings.

N-gram range will be set to (1,1) or (1,2) to include individual words and adjacent word pairs in the bag of words model.

ML Technique #2: Latent Semantic Analysis (TruncatedSVD in scikit-learn)

Dimensionality reduction is a useful technique that can assist ML algorithms in more quickly converging on a solution by combining variables into n component features that each combine related features. LSA is similar to PCA in that it applies singular value decomposition to find a transformation that rotates axes in a manner that projects the data to a lower dimensional feature space. The main difference is that LSA accepts a sparse term-frequency matrix – obtained here through CountVectorizer – and obtains an approximation by computing three matrices: a term-concept matrix, a singular values matrix with eigenvalues on the diagonal, and a concept-document matrix. These three matrices produce an approximation of the original term-frequencies matrix.

As discussed in the approach section of the readme file, dimensionality reduction will only be applied to the SVM classifier as Naive Bayes requires discrete data.

| Combination | n_components |

|---|---|

| 1 | 525 |

| 2 | 775 |

| 3 | 1180 |

With scikit-learn’s PCA implementation, we could specify a floating-point number for n_components to indicate what percentage of explained variance we would like to retain in the dataset with our chosen components. However, scikit-learn’s implementation of LSA only accepts an integer for the n_components parameter.

Since our value for the n_components parameter is dependent on the number of words in our dataset – which relies on the choice of ngram_range for CountVectorizer – we will determine optimal parameters for our experiments after running an initial grid search for the first two pipelines. Using optimal parameters, we will then fit a model using CountVectorizer and TruncatedSVD and determine number of components that retain approximately 85, 90, and 95 percent of explained variance in the dataset. The values in the above table reflect this approach.

ML Technique #3: Support Vector Machine (SVC in scikit-learn)

The Support Vector Machine is one of two classifiers that will be used in this experiment. SVM have been known to do well in applications for text classification with high dimensionality where the dataset is not too large. For this application, a balanced training set will contain approximately 5,000 records, which is suitable for SVM.

| Combination | kernel | C |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Linear | 1 |

| 2 | Linear | 10 |

| 3 | Linear | 100 |

| 4 | Linear | 1000 |

The main choice in configuring SVM is the choice of kernel, followed by the appropriate hyperparameters asscoaited with that kernel.

A linear kernel will be used in this experiment as many applications of text classification can be linearly separable, particularly as a result of the high dimensionality and large dataset sizes for text classification datasets. Linear classifiers are also much faster to train and only require tuning of the regularization parameter C. For this experiment we will test values of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 for the C parameter.

If it is found that the SVM does poorly with a linear kernel, additional experiments will be conducted with other types of kernel to see if performance improves.

ML Technique #4: Naive Bayes (Bernoulli Naive Bayes in scikit-learn)

Since our bag of words model uses binary frequencies of 0 or 1, we use the Bernoulli Naive Bayes classifier in scikit-learn, which is optimized for binary counts.

| Combination | binarize | alpha |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | 0 |

| 2 | None | 0.1 |

| 3 | None | 0.5 |

| 4 | None | 1 |

The binarize parameter is set to None in all instances to disable the conversion to binary counts since this has already been performed by CountVectorizer.

The alpha parameter controls the level of smoothing applied in the training set. This can be useful when items in the test set would have zero probability based on the training set. There is no good rule of thumb for setting this parameter, so the experiment will include several values within a parameter Grid Search.

Results

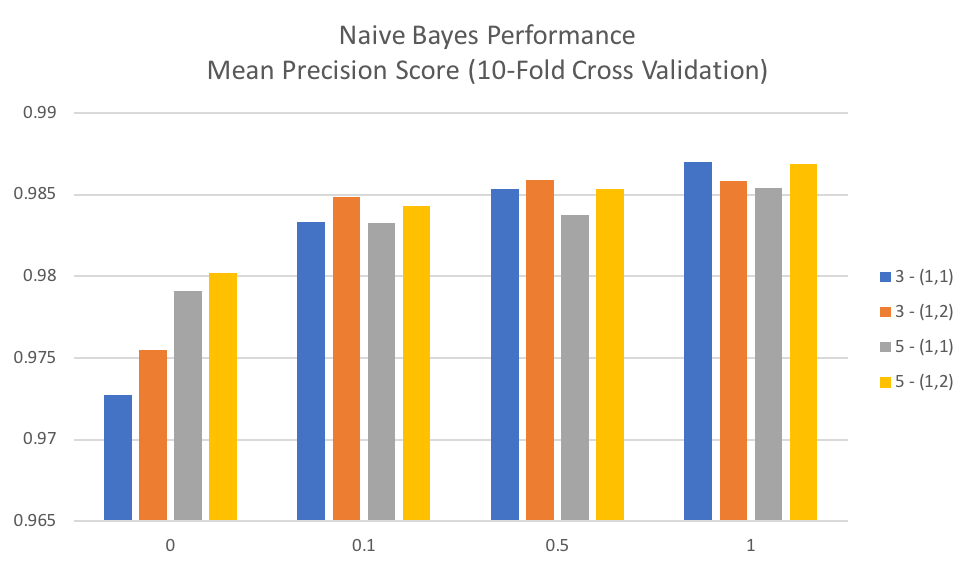

Naïve Bayes

The alpha parameter is the main hyper-parameter adjusted in Naïve Bayes and controls the level of smoothing applied to the model, accounting for features in the test set not encountered in the training set and would otherwise compute a probability of zero.

The below graph shows mean precision score over 10-fold cross validation for each value of alpha tested and is grouped by values for min_df and ngram_range used in CountVectorizer. We can see that an alpha value of 1 (the default Laplace smoothing using in scikit-learn) results in the best average precision score and that in general lower values for alpha (Lidstone smoothing) result in lower average precision scores. In general, we can also see that for Naïve Bayes that including bi-grams (ngram_range = (1,2)) generally performs better than the alternative of singles words in the term-frequencies matrix.

The grid search object returned by scikit-learn also returns basic statistics on average time to fit and score each combination of parameters. Naïve Bayes is popular as it is relatively fast to both train and make predictions. For this particular dataset, there was an average fit time of 0.0987 seconds and an average scoring time of 0.0104 seconds.

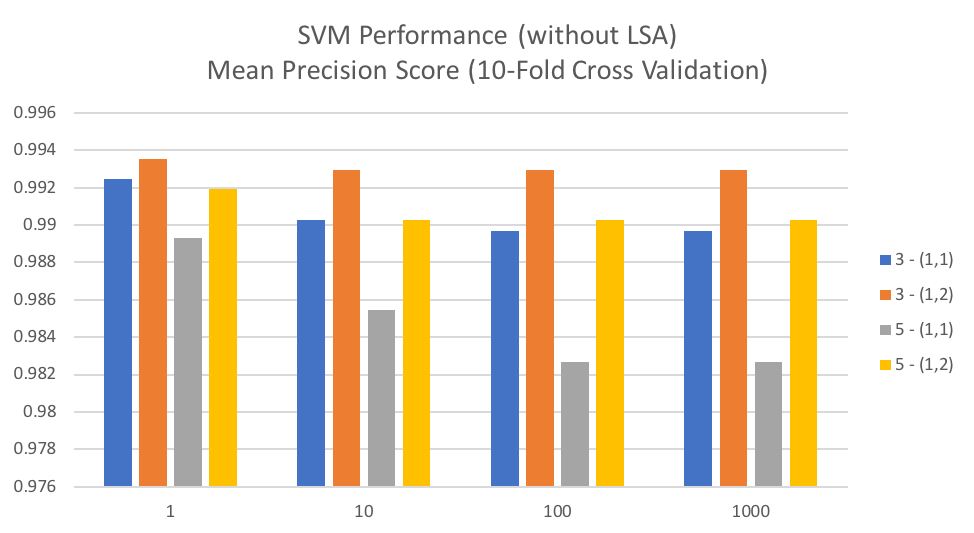

Support Vector Machine without Dimensionality Reduction

Using a linear kernel, the C parameter is the main hyper-parameter adjusted for the Support Vector Machine and controls the error penalty used when misclassifying an example. Larger values of C generally mean a smaller margin around the separating hyperplane.

The below graph shows mean precision score over 10-fold cross validation for each value of C tested and is grouped by values for min_df and ngram_range used in CountVectorizer. We can see that for this particular dataset a smaller value of C generally results in a better classification score, particularly when min_df is set to 5. For min_df of 3 there is a very small difference. In general, we can also see that including bi-grams (ngram_range = (1,2)) generally performs better than the alternative of singles words in the term-frequencies matrix.

Support Vector Machines can be problematic in that they are slow to train for larger datasets. However, for this particular dataset, it worked fairly well with an average fit time of 0.2176 seconds and an average scoring time of 0.0190 seconds.

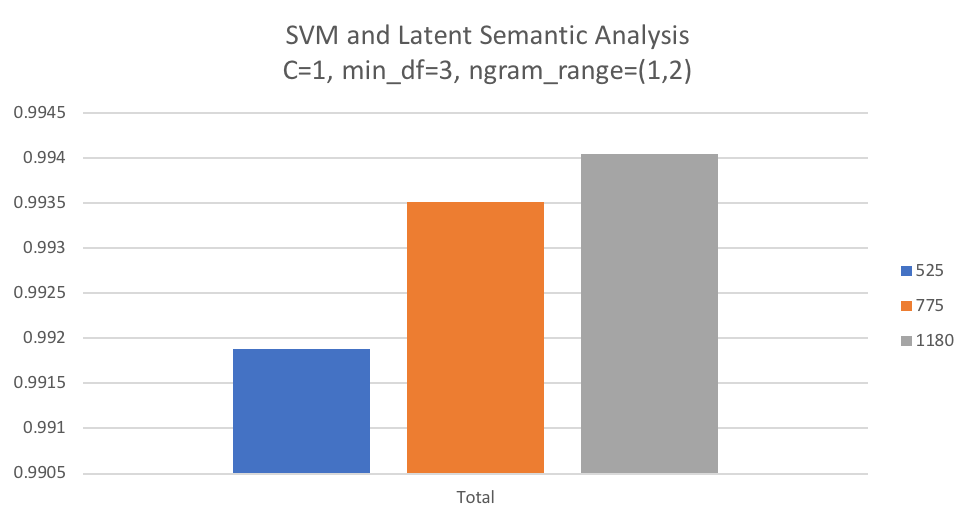

Support Vector Machine and Latent Semantic Analysis

As discussed in the Experimental Plan, the n_components parameter for TruncatedSVD/LSA is dependent on the number of features in the dataset and is therefore dependent on the parameters set in CountVectorizer. After running grid search against Naïve Bayes and SVM, we selected chose the best performing estimator and parameters, which was SVM with C=1 and CountVectorizer using min_df=3 and ngram_range=(1,2). Using these parameters, the training model was fit using a variety of values to determine the approximate number of components that would result in 85, 90, and 95 percent of explained variance given the dataset. This resulted in the chosen values 525, 775, and 1180.

The below graph shows mean precision score over 10-fold cross validation for each value of n_components tested with LSA and SVM. We can see that in general the larger values of n_components that retains explained variance results in better precision scores. Given this finding it will be interesting to see whether LSA provides better performance than when all terms are retained in the dataset.

With LSA added to the third pipeline for grid search, it computed an average fit time of 5.67 seconds and an average scoring time of 0.1321 seconds, significantly longer than Naïve Bayes and SVM without dimensionality reduction.

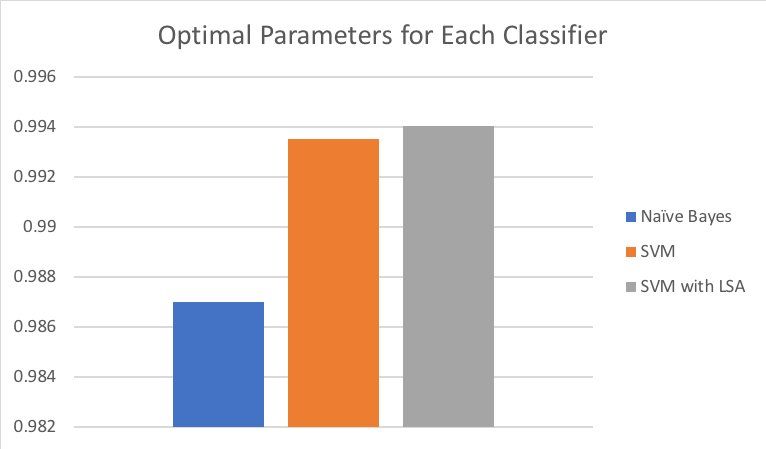

Comparison of Three Options

The below chart includes a side-by-side comparison of the average precision scores for 10-fold cross validation using optimal parameters for each classifier option. Both Naïve Bayes and SVM options work particularly well for this application, with average precision above 98 percent. The top performing classifier was SVM in conjunction with LSA retaining 95 percent of explained variance.

As discussed in prior sections, SVM can be problematic for larger datasets and when adding LSA we saw an additional 20 times increase in computing time. This is worth considering for training sets that surpass millions of records. However, in this scenario we will choose the SVM with LSA option in scoring against our test dataset.

Performance with Test Data

Using optimal parameters for CountVectorizer (min_df=3, ngram_range=(1,2)), TruncatedSVD/LSA (n_components=1180), and SVM (kernel=linear, C=1), models were fit to the training data and then test data was transformed.

Predicted class labels were obtained for each transformed row in the test set and a classification report was produced in scikit-learn (below) which provides precision, recall, and F1 scores for each class label.

| Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-DMI | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 621 |

| DMI | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 627 |

| Avg/Total | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 1248 |

The original problem statement noted that we were particularly interested in maximizing precision and specificity for the DMI class in order to correctly classify DMI deaths while avoiding false positives. The results for our test data show that we have 99 percent precision and specificity for the DMI class (Note: for binary classification, specificity is the same as recall for the negative class).

A confusion matrix was also produced for the test data (below) and shows that for the Non-DMI class only 8 records were misclassified and for DMI only 15 were misclassified.

| Actual\Predicted | Non-DMI | DMI |

|---|---|---|

| Non-DMI | 613 | 8 |

| DMI | 15 | 612 |

Conclusions

In this project, we linked annual death statistical files and cause of death literal text files from the State of Washington and used this data to train Naïve Bayes and Support Vector Machine classifiers to distinguish with high precision and specificity whether a given record was a drug mention with involvement death (DMI) or not. Natural language processing techniques were used to remove stop words and punctuation, as well as to convert the linked data to a matrix of term frequencies using unigrams and bigrams. The optimal classifier, Support Vector Machine using Latent Semantic Analysis for dimensionality reduction, achieved precision and specificity of approximately 99 percent for the DMI class on test data. The model exceeded expectations set by exact pattern matching programs, which identified DMI deaths with 95.8 percent precision.

The success in this experiment is largely attributed to the amount of work in cleaning and preprocessing the data, including the use of natural language processing techniques. With additional cleaning, I believe the model could be further improved. One thought within NCHS is to incorporate systems such as UMLS from the National Institutes of Health, which provide an extensive thesaurus of millions of biomedical concepts and can be used to map synonyms and variations of a term to a principle concept. Reducing the number of terms/features, as we did with LSA in this experiment, improves the ability of the classifier to find an optimal solution.